3 de noviembre 2023

European Concern over Lack of Academic Freedom in Nicaragua

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

Since 2018, under the de facto police state, CABEI's executive president granted Ortega USD 2068.5 million

Confidencial

During the five years that Dante Mossi presided over the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI), the regime of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo received nearly the same amount of funding from this regional institution as they did during the ten-year tenure of the previous president, Nick Rischbieth. This fact shows Mossi’s closeness to the couple that controls the reins of political power in Nicaragua.

In early September 2022, former U.S. Ambassador John Feeley, executive director of the Center for Media Integrity of the Americas, urged the U.S. Treasury Department to take a closer look at CABEI, “led by an individual named Dante Mossi, who has become the banker to dictators.”

The following year, the CABEI allocated 62 million dollars less to the dictatorial couple, although it also reduced disbursements to the rest of the founding countries of the bank. On the other hand, it increased disbursements by more than 1.1 billion dollars to extra-regional (or non-founding) partners such as Argentina, Belize, Colombia, Panama, and the Dominican Republic, according to official information disclosed by Dante Mossi through his profile on social network X.

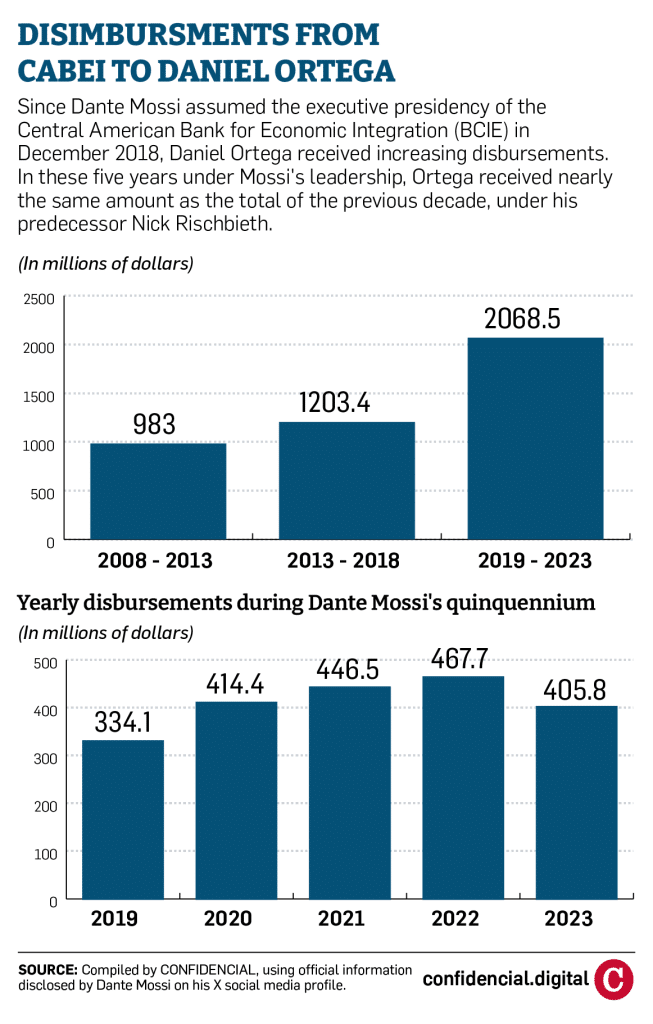

During Rischbieth’s first five-year term (December 1, 2008 to November 30, 2013), CABEI disbursed 983 million dollars to Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega. That figure grew by 220.4 million dollars (22.4% more) during Rischbieth’s second term, reaching 1203.4 million dollars.

However, when Dante Mossi assumed the Bank’s executive presidency on December 1, 2018, he began increasing the flow of resources that bolstered the budget available to Ortega and Murillo: 334.1 million dollars in 2019, followed by 414.4 million in 2020, 446.5 million in 2021, and 467.7 million in 2022, and decreasing in 2023 to 405.8 million.

The total for these five years amounts to 2068.5 million dollars, exceeding the disbursements received in the previous five-year period by almost 72%. This increase was so disproportionate that the amount received in those five years is almost the same (94.6%) as the funds that the Bank delivered to Nicaragua during the ten years Rischbieth presided over it (2008 - 2018).

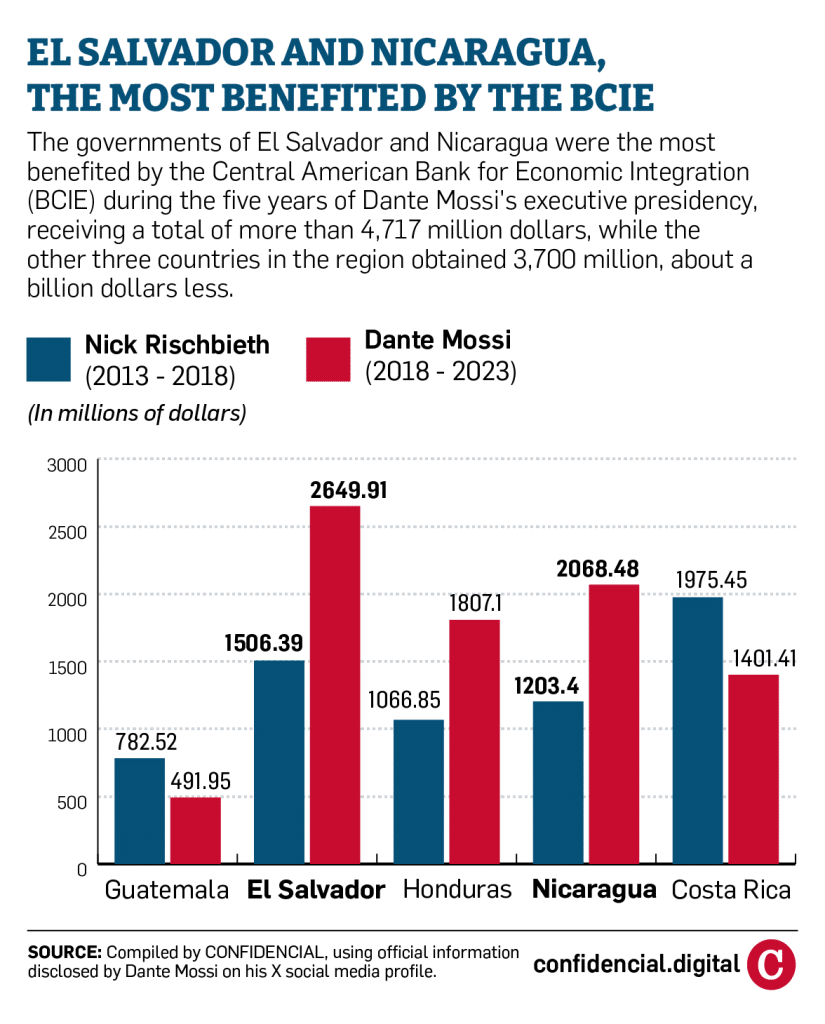

Another way to grasp the significance of the decisions implemented by the Central American Bank under Mossi's presidency is that, during those five years, Nicaragua received 24.57% of the disbursements made by this regional institution, ranking second after El Salvador, which received 31.48%.

Behind them are Honduras with 21.46%; Costa Rica with 16.65%, and Guatemala, the most populous nation in the isthmus, receiving only 5.84% of the funds disbursed. This is explained by the fact that Guatemala prefers to finance itself with other sources of funding that are more cost-effective than CABEI’s.

There is no single theory to explain Dante Mossi's generosity towards authoritarian regimes in Central America. To provide another comparison: during the decade when Rischbieth presided over the Bank, Nicaragua received approximately 599,000 dollars per day, while with Mossi, the Ortega-Murillo regime was blessed with an average daily amount of 1.13 million during those five years. El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele fared even better, receiving a total of 2,649.9 million, equivalent to 1.45 million dollars daily.

The most direct responses come from two former Costa Rican officials at the Bank. Ottón Solís, a former representative of his country at the regional financial institution, claims that “Dante was fascinated with his re-election. He did everything to seek the support of the countries.”

His compatriot Eduardo Trejos, also a former Bank official, adds that Nicaragua turned CABEI into its main financial institution when Ortega and Murillo realized that Mossi was willing to cooperate “in all aspects to obtain the vote of the Nicaraguan government in favor of his re-election.”

Due to this, he believes that the new Bank administration should thoroughly engage in verifying the supervision of projects that may be mismanaged, which would be “regrettable.”

Another economist who also worked for the Bank admits that it amuses him every time someone says that Mossi favors Ortega or Bukele. He insists that such an allegation is not correct, as he believes that “ it would have been the same with any other president. Even with the most independent president you can think of, it would have been the same, or almost the same, because there is no democratic clause” within CABEI.

Another reason is that even if Mossi had decided to change course (by his own will or under pressure), the Bank still would not have been able to limit the dictatorship's access to its resources. Firstly, because Nicaragua is a co-owner of the Bank. Secondly, there is a series of signed contracts that must be respected in the absence of a democratic clause.

The third reason is that if they stopped lending money to Ortega and Murillo on behalf of Nicaragua, the dictatorial couple could intentionally lower the Bank's credit rating by simply failing to pay on time, which would have increased the financial costs for the Bank as an institution and for its institutional or business clients.

Additionally, he pointed out that the countries have a pre-assigned quota, according to their shareholding, and this portion is adjusted according to the numbers of each context. “That is why capitalization was so important for Mossi and for those countries, [and by not doing so] today they are very limited,” he explained.

The outgoing CABEI president called for three capitalizations. The first in 2020, to bring the Bank's capital from the US$5 billion at which he found it, to US$7 billion. But in September 2022, and in May 2023, when he tried to raise it to $10 billion, the governors told him no.

The first time Mossi asked to raise it to $10 billion “it was rejected because it was [technically] bad. It was a disaster. It was a piece of toilet paper. The other reason for such a rejection is that the other partner countries also have to agree.” The problem for Mossi is that the second proposal was also “technically bad,” he said.

In addition, he assumes that the fact that the Central American countries did not want to pay their share also played a role, as was the case when the amount was increased from US$5 billion to US$7 billion, and the Bank allowed them to pay in installments, a financial decision that weakens any capitalization process.

Of the $983 million disbursed during Rischbieth's first term, there was $120.7 million for road construction. In Rischbieth's next five-year term, with a total of $1411.6 million in disbursements, more than half ($783.3 million) went to fund road construction programs, including $105.5 million to build the Pista Juan Pablo II and several overpasses in Managua.

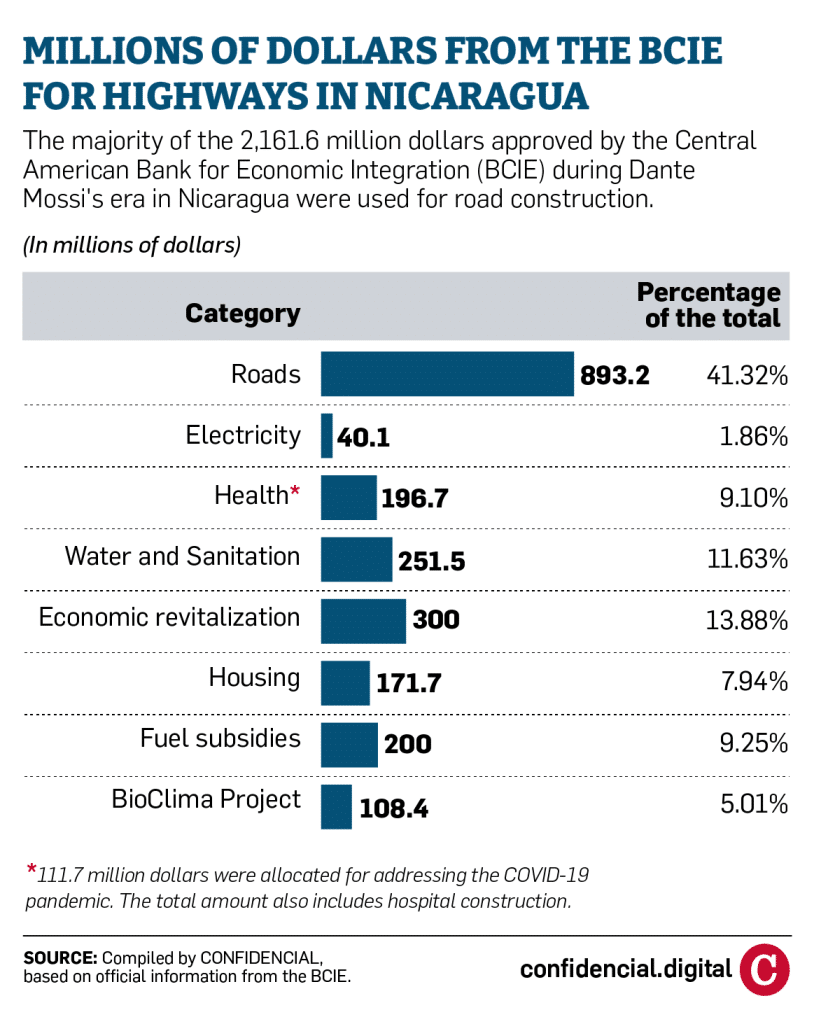

Roads continued to be the most prioritized sector during the Mossi era, which is about to end, with 893.2 million approved for that sector, which is equivalent to 41.3% of the 2161.6 million of that period, according to official data published by CABEI, which is some 93 million dollars more than those reported by Mossi in his social network X account.

The next amount in order of importance in the disbursements of this five-year period is the 300 million destined for economic reactivation, as well as 251.5 million for the potable water systems of seven Nicaraguan cities.

There are also 200 million in fuel subsidies and 196.7 million in health, of which the majority (111.7 million) were approved to attend to the emergency caused by the COVID-19 epidemic, despite the evident lack of interest shown by the dictatorship in facing this life-threatening tragedy.

Finally, 171.7 million was approved for a social housing program that was delayed for a year, 108.4 million for the Bio-Clima project, and 40.1 million for the Bluefields substation.

Between 2009 and 2017, the Bank also allocated 137.25 million dollars to ten private sector companies. The largest loan went to one of the Pellas Group companies, although the sum of several other placements shows that the privileged one was the financial sector, according to a database compiled by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

The year with the highest number of approvals was 2009, when four projects were given the green light: three productive and one credit project. All were small amounts, totaling only $2.05 million, of which $1 million went to an agriculture and rural development project.

The remaining amount was divided into three small loans: one for Manuquinsa, for a quarter of a million dollars, and another for Repsa, for US$300,000, both under the heading of “production chains.” The remaining half a million dollars was used to finance Credifactor's lending operations.

In the following years, although in dribs and drabs, larger amounts were approved to support more ambitious projects, such as the US$10 million earmarked for the Amayo wind power project in September 2010, or the US$25.5 million made available to Hidropantasma in February 2011.

In May of that same year, the Bank contributed $46.7 million to the Guacalito de la Isla tourism megaproject, owned by Pellas Development, after which it limited itself to approving three more projects, every two years: $3 million for social development in May 2013, which would be followed by two lines of credit: one for Lafise for $40 million in February 2015, and another for Ficohsa for $10 million, in May 2017.

When former US Ambassador John Feeley referred to Dante Mossi as “the banker of dictators” in September 2022, perhaps he said it because most of the Bank's active operations during these five years were focused on Nicaragua, a country with poor governance and even less transparency, or because of the support given to former President Hernandez of Honduras during his electoral campaign, or to the other strongman of the region: the Salvadoran Nayib Bukele.

Various sources who spoke to CONFIDENCIAL to build a profile of the bank's executive president, assured then that – in addition to the 'gratitude' that Mossi owes to the governments of those three countries – it was his intention to guarantee votes to be reelected for five more years.

However, in May 2023, CABEI's Board of Governors, meeting in the Dominican Republic, made the surprise unanimous decision not to offer him a new five-year term as executive president, opening a selection process that now leads to the election and appointment of a new official in November. It remains to be seen if whoever takes over from Mossi as executive president will bring winds of change to CABEI.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense, exiliado en Costa Rica. Durante más de veinte años se ha desempeñado en CONFIDENCIAL como periodista de Economía. Antes trabajó en el semanario La Crónica, el diario La Prensa y El Nuevo Diario. Además, ha publicado en el Diario de Hoy, de El Salvador. Ha ganado en dos ocasiones el Premio a la Excelencia en Periodismo Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal, en Nicaragua.

PUBLICIDAD 3D