31 de octubre 2023

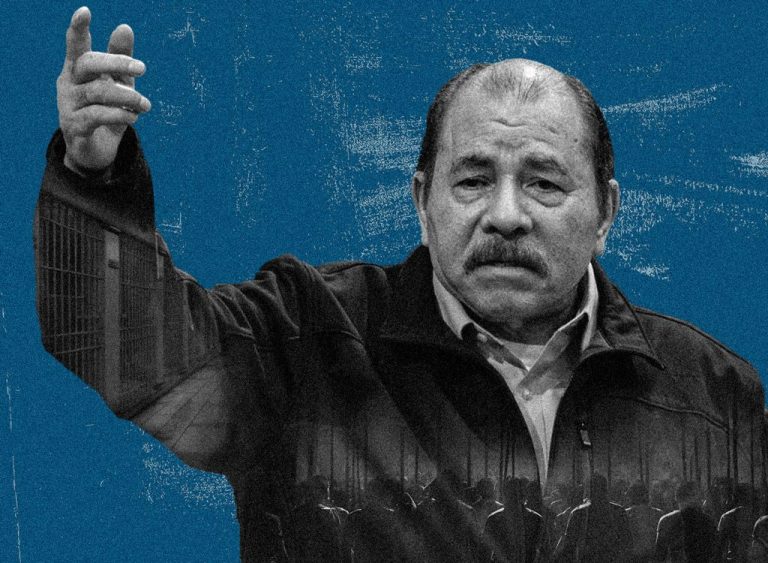

European Concern over Lack of Academic Freedom in Nicaragua

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

After the banishment of 222 political prisoners in February, the dictatorship has once again filled the prisons with 80 prisoners of conscience

There are currently more than 130 political prisoners being held by the dictatorship of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo. This is after the release and banishment in February of 222 political prisoners, and then of twelve priests who were being held as prisoners of conscience in October. More than 80 of these political prisoners are incarcerated in seven prisons in different provinces of Nicaragua, according to reports from the Mechanism for the Recognition of Political Prisoners and the Blue and White Monitoring group. In addition, another 60 remain under de facto house arrest or "city confinement," obliged to sign in daily, weekly or biweekly at assigned police stations, according to newspaper reports.

Among the prisoners is Bishop Rolando Alvarez, arrested in August 2022 and incarcerated since February 2023 in a maximum security cell with a sentence of 26 years and four months. Lawyers and analysts consider that the release and banishment of the twelve priests is a measure taken by the regime to "alleviate international pressure" demanding the release of political prisoners. However, the dictatorship has once again filled the country's prisons with political prisoners in record time, all the while increasing political surveillance and continuing to violate civil liberties across the five years of a de facto police state.

In the eight months following the release and banishment of 222 prisoners of conscience –which included political and civic leaders, journalists and business leaders– Ortega continued to imprison citizens through both massive and selective raids, imposing new repressive and illegal measures, such as house arrest or a "city confinement" designation.

As of July, the Mechanism had identified 78 people as prisoners of conscience. In its next report in August, it raised the number to 89. Of the 11 Nicaraguans added to that month's list, five were detained in April, one in June, one in July and four in August. The Mechanism clarified that official registrations take time due to the necessary verification work that goes into recognizing a political prisoner. Another factor is the fear family members have of the possible consequences of publicly denouncing their loved one's detention.

An analysis by CONFIDENCIAL with data from the Mechanism, verified that at least 34 Nicaraguans registered as political prisoners as of March 2023 (after the release of the 222) remain in Ortega's jails, among them ten political prisoners from before the repression against the citizen protests that broke out in 2018.

In April, the Ortega police carried out new raids, focusing on repression against the Catholic Church and anyone who commemorated the fifth anniversary of the 2018 civic protests. Officials persecuted parishioners who defied the order not to carry out processions on public roads during Holy Week, and later, they carried out arrests of opponents, activists, journalists, and territorial leaders.

Student leader Jasson Noel Salazar Rugama, former political prisoner Olesia Muñoz, young entrepreneur Anielka García, journalist Víctor Ticay, and former political prisoner Abdul Montoya are some of the 40 people detained in April who are still in prison, according to the Mechanism.

At least a dozen of the political prisoners captured in April received sentences of between eight to ten years in prison for the fabricated crimes of "propagation of false news" and "undermining national integrity." Montoya is the exception, having been sentenced to 23 years in prison because of additional charges of terrorism. Arrests continued in May, June and July, but were more selective.

In August, the police arrested three university leaders: Adela Espinoza Tercero, a graduate of the Social Communication program at the UCA; Gabriela Morales, from the canceled Juan Pablo II University, and Mayela Campos Silva, a third year student of industrial engineering at the National University of Engineering (UNI). They were joined by sociologist and activist Melba Damaris Hernández and former political prisoner Juan Carlos Baquedano, captured on the third day after his return from exile in Mexico.

The women political prisoners were transferred to La Esperanza prison and Baquedano to La Modelo, both located in Tipitapa. The status of their respective trials is unknown.

The most recent political prisoners are Yatama's National Assembly representative, Brooklyn Rivera, and his alternate, Nancy Henríquez.

Rivera was arrested on Friday, September 29, after a raid on his home in the city of Bilwi. The regime prevented his reentry into the country in April 2023, but the legislator entered irregularly through the Mosquitia and since then has been under surveillance. Henríquez was detained on October 1, under the pretense that she would be interviewed in relation to Rivera's case.

Hunting down priests in Nicaragua

Between May 20 and 23, the Ortega regime began a new escalation against the Catholic Church, imprisoning priests Pastor Eugenio Rodríguez Benavides and Leonardo Guevara Gutiérrez, who were placed under investigation in "seminary confinement" at the National Seminary of Our Lady of Fatima, in Managua.

On May 25, the police confirmed the arrest of priest Jaime Ivan Montecinos Sauceda, under investigation for treason. On July 9, Father Fernando Zamora Silva was arrested, and on September 8, Father Osman Amador Guillén was detained. Finally, in the first week of October, the police arrested six priests, bringing the total to 14 priests being held under some kind of confinement measure.

In addition to the three convicted priests –Leonardo Urbina, Manuel García and Bishop Rolando Álvarez– four of those arrested were taken directly to prison, and one, Father Leonardo Guevara, was released. The remaining six, who had been left in "seminary confinement," were transferred to the Auxiliary Judicial Complex "El Chipote," and then banished with the rest. In total, twelve priests were sent by the dictatorship to the Vatican on Wednesday, October 18.

Although the Police never justified the arrests of the priests between May and October, some advocates warned that all clerics were at risk of being imprisoned after the Police announced an investigation for alleged money laundering against the Catholic Church on May 27, 2023.

At least 60 are under house arrest or "city confinement"

There are about 60 other "politically processed" citizens. Most of them were arrested in raids in May, carried out by the Police in coordination with the Public Prosecutor's Office and the Judiciary. They were kidnapped, then subjected to "express" hearings to charge them with "undermining national integrity" and "propagation of false news." All are on "probation," but must sign in daily at police stations.

This same pattern was repeated in September and October against parishioners of the Catholic Church, mainly in the north of the country –where the repression against the dioceses of Matagalpa and Estelí has been concentrated– and in Boaco and Chontales. The Police summoned more than a dozen citizens to inform them that they are being investigated and that they are being held in "city confinement"; that is, they cannot leave town. They must also sign in at police stations on a weekly or biweekly basis. In addition to these citizens, there are other Nicaraguans who have been taken by the police, whose cases are not reported by their families for fear of reprisals, thus increasing the underreporting of arrests.

The activist and former political prisoner, Ivania Alvarez, does follow up work from exile on the cases of political prisoners. She says "there is underreporting" due to families' fear of going public with a denunciation. Taking into account this underreporting, she says, "we could be talking about almost 200 political prisoners right now." After the release and banishment in February, there were 35 political prisoners still on the official list.

"This is happening in record time, because before, it took more than a year to reach those numbers. Now there are almost 200 people who are subjected to some kind of judicial process, either in conditions of home or city confinement with periodic reporting, or in the different penitentiary centers of the country," Alvarez explains.

She adds that this underreporting is maintained by fear among the population and by the lack of venues to make denunciations. The mass exile of activists, human rights defenders, and members of civil organizations who no longer operate inside Nicaragua, make it more difficult to document the violations.

Alvarez points out that denunciations are important because "on the surface it would seem that the list of political prisoners in Nicaragua has not grown, when this is not actually the case."

This article was originally published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by our staff.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Confidencial es un diario digital nicaragüense, de formato multimedia, fundado por Carlos F. Chamorro en junio de 1996. Inició como un semanario impreso y hoy es un medio de referencia regional con información, análisis, entrevistas, perfiles, reportajes e investigaciones sobre Nicaragua, informando desde el exilio por la persecución política de la dictadura de Daniel Ortega y Rosario Murillo.

PUBLICIDAD 3D