European Concern over Lack of Academic Freedom in Nicaragua

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

I still remember his starched white cotona with wings

So now the revolutionary poet-priest has passed, and the newspapers are replete with the story of his poetry and radical views, his struggle against the Somoza regime, his participation as Minister of Culture in his country’s revolution and reconstruction, as well as his expulsion from the priesthood, his subsequent opposition to the Ortega appropriation of Sandinismo, and then the persecution he suffered as the Ortegas sought to discredit and break him in his last years. I won’t try to go over this trajectory but will rather recount some of my experiences with him during the Revolution and in the years which followed, to give you my sense of who he was to me and probably to others as well.

In 1970, living near the San Diego/Tijuana border, I married a Nicaraguan fellow graduate student; and by 1972, I was reading Nicaraguan poetry, above all the famous Epigramas and Salmos of Ernesto Cardenal. By that time also, I had joined my then wife in solidarity with the Sandinistas, and had even participated as a naïve chauffeur for some relatives who turned out to be part of Managua’s anti-somocista urban guerrilla. With the earthquake of December 1972, and yes, in part driven by the death of Roberto Clemente, we joined in helping to provide food and clothing to be shipped to Managua; and in subsequent years, as literature students, we also began developing a book using the poetry of Cardenal and other poets in an image-driven “collage history” extending from the early days of U.S. intervention and dictatorship to the development of a successful revolutionary movement which led to the victory of July 19, 1979. As the Sandinistas came to power, my wife won a leave of absence and I quit my job so that we could participate in the Revolution. As I told a friend, “I’m forty years old, believe in the revolution, haven’t done much in my life and now have maybe my first and only chance to do something meaningful. So here we go.”

We had complications, but we got to Managua with our son in September 1979, where we started looking for a place to live, but realized we couldn’t really choose one until we knew if and where we could work. “We have to go to the Ministerio de Cultura and present ourselves,” my wife said. And off we went, without much preparation beyond photocopying our resumes and buying a fresh binder for our book manuscript, Nicaragua in Revolution, entering the doors of the Ministry without an appointment, going directly to the front office and asking if it was possible to see the head man, the poet Ernesto Cardenal, that very day.

“Well, his schedule’s pretty full,” said the receptionist who tried to look stern but couldn’t hide her natural friendly way. “But you know, he’s in the dining area having lunch, so why don’t we look for him there, to see when he can see you.”

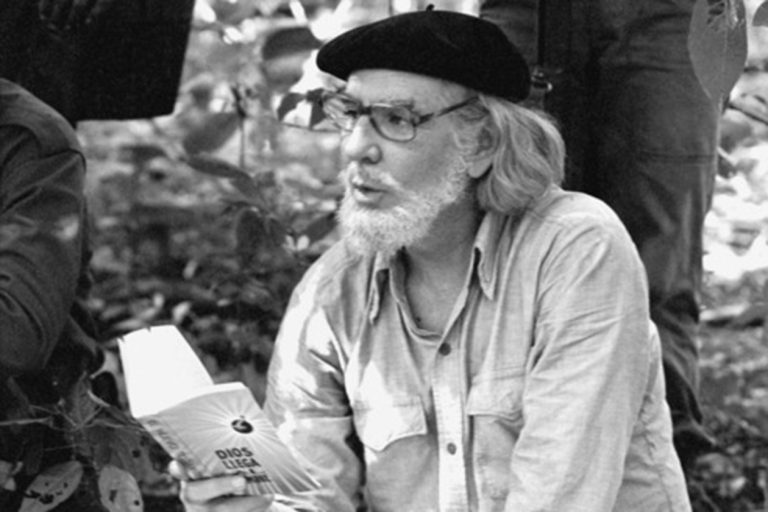

Just like that she escorted us to the ministry’s cafeteria, a place buzzing with hungry artists, some of them painters, clowns, singers—whatever. There, at one corner table sat the famous poet in his customary beret and peasant shirt, or cotona, eating but also engaged in a discussion of one thing or another, with several scruffy looking teenage revolutionaries.

“Poeta,” said Berta, “here are two compañeros—they wanted to know when they could meet with you.”

“Ahuh,” said the revolutionary poet-priest, standing up and offering his hand.

“We’re literature professors, I’m nicaragüense and he’s an American and

we’ve both come to Nicaragua to see if we can offer our help,” said my wife.

“Ah, you’re looking for jobs,” said the poet.

“Not exactly, but we’ve taken a year off from our jobs to see if we can volunteer our services.”

“No,” said the poet, “we need people ready and able to work for low wages, but volunteering is too informal and unfixed. Did you bring your resumes?”

“Yes,” she said.

“Good,” he answered. “Why don’t you sit down with us for lunch, and then we can go upstairs and see what kind of work you might be able to do for la Revolución.”

Almost at a loss for words, we plopped ourselves down and soon were served plates of rice, beans and chicken, with a tropical fruit drink and then a piece of pie and coffee for desert. Before we knew it, we were sitting in the Minister’s office while he poured over our resumes seemingly impressed with our experience as professors, critics and theoreticians. But what could he do with two Ph.D. academics?

“Maybe you should be looking for work at the university,” he suggested.

“We thought we might do some teaching,” my wife said. “But maybe we could do something more than that. We’ve both worked with poor families in Mexico and the U.S. …“

“Yes,” he said, “I see you’ve worked with farmworkers,” he told me.”

“Yes…”

“But that’s very different from working with our peasants.”

“Yes,” I concurred, “but I’m pretty good adjusting my skills.”

“What’s this book manuscript you mention about Nicaragua?” he asked; and I handed him the copy we’d prepared. Immediately the poet began turning the pages.

“We cut up your poems,” I said, trying to somehow anticipate and offset the poet’s possible shock.

“But why would you do that?” he asked, looking up with the most pained expression, as if on the verge of tears, as if we’d killed his dear children.

“We thought we could weave the poetry to tell the history of Nicaragua.”

“Oh,” he said, fanning the pages, bobbing his head rabbi-like… “Not bad,” he said… looking up at us, trying to size us up. “It’s a good idea, the book will be beautiful.”

“We need your signature to give us the right to publish the poetry and our translations. “

“That’s no problem,” he said. I’ll have our legal staff draw up the papers—by next week.”

“You’re nica,” he said, eyeing my wife, changing the subject oh so quickly.

“My whole life,” she said joking.

“But you don’t talk nica.”

“I’ve lived most of my life in Mexico and los Estados, but I’ve also lived here and I can talk nica if you want.”

“I like what I see,” said the poet. “I think we could use your skills and experience, I think we can. Let me check around and talk to Daisy Zamora—she’s a fine poet who’s heading our literature section. Leave Bertha your telephone number, and we’ll call in about a week.”

A week to the day we received the call from the ministry to meet with Cardenal and Zamora the next day. When we arrived, the two poets greeted them with the most serious

“We’ve done all the checking and talked over everything. We had our Chilean assessors check you out with our pro-Allende friends in the U.S. and you got the highest ratings,” he told them, as my wife responded almost in shock, given her difficult relationship with the Chilean professor in her university.

“This is a young people’s revolution, and it’s not easy being older in this climate. But we think there’s a lot you can help us with.”

Daisy seemed less convinced; she seemed shy and a bit unhappy to be dealing with a yanqui professor type, let alone with a nica literature Ph.D. who didn’t write poetry but clearly had a superior academic profile. Daisy had been part of the revolution, and who were these Ph.D. interlopers? Cardenal seemed to be addressing her as well as the couple as he mentioned the generation gap.

“We’ve decided to form a two-pronged literature section,” he told them. “There’ll be you two and another professor, handling the professional side of things—the publications and presentations, interviews of visiting writers-- a whole range of things--and there’ll be three young poets who’ll work with the local committee setting up cultural centers in schools, factories and residential areas.”

“You’ve got to be ready to move around the country. The revolution’s not just Managua, and you’ve got to use different skills in different contexts,” Cardenal said.

“But first you’ve got to go to personnel to get on the payroll. We can only offer each of you the maximum we pay here—500 cordobas a month. But we can get you a good place to live—there’s a house that’s become available in Villa Panama, and you can have it as an addon to your pay but with one stipulation.”

“And what’s that?”

“You have to keep the place up and keep the servants.”

“But I’ve never had servants,” I objected. “And this is a revolution.”

“This is a revolution with a lot of poor people who need to hold on to their jobs until we can create a new social structure with good jobs for all. In the meantime we can’t fire everyone in the name of democracy. Everything is going to change. But not from one day to another,” said the poet.

And there it was: a kind of pact with the devil. We had thought we would live in a tent or a hovel but were now to occupy and maintain the class/caste/race structure in an L.A. style confiscated suburban house in one of the plushest areas of Managua. Sure enough, it was better than any place I had ever lived in—a modern home with air conditioning, a servants’ quarter, a play area and much more—all too good to be true.

The first days at work were ones of confusion. Soon Daisy called Cardenal to meet with our group. “You are the most important unit in the Ministry,” the poet told them. “But I am the Minister of culture and not the minister of literature. As your leader, I cannot afford to be seen as favoring your section or paying much attention to it. But you know my heart and soul is with you. This is a country famous for its poetry. Now all Nicaraguans can be poets. But for that we need the literacy campaign, and that’s not your specialty, I know, and the campaign won’t begin until the spring. What I ask is that you prepare the way for the great literature that the revolution will bring to the fore. To carry out our overall program, Daisy will now leave the section to be my. Sub-Minister, and a brilliant young poet, Julio del Valle will join the section as its new director”

Two major events occurred in those first months which spelled out and limited our work. First Cardenal came to our weekly section meeting. “I wanted to let you know, compañeros, that we’re starting a new cultural journal which will involve literature and be something like Cuba’s Casa de las Americas journal, but claro, very different. I’m trying to think of a name and wonder if you might have an idea.

“El Despertar!” said one.

“Amanecer!” another suggested.

“Well, I was thinking of something indigena,” the poet-minister said. “something like Nicarauac…’’

“Fantastic!” said Julio in his first week as our new director; and Julio was right to do so, since he had to know that the poet-minister had this name in mind before he came to our session.

“But why did he bother to ask us?” asked one of the young section member.

“So he could always say he consulted, that he didn’t make the decision on his own,” said my wife.

“Ah,” I said, sensing I’d just learned something new about the revolution and my boss.

Then too, I remember the day in November, when, representing the Literature Section, we were sent to Ciudad Darío to help in the logistics for what Cardenal called El Maratón de Poesía. a popular event featuring the budding poetry workshops being developed by Costa Rican poet/teacher Mayra Jiménez and her staff on the model of Cardenal’s workshops in Solentiname, but also poetry writing groups developed by our section members. I remember arriving soon after dawn, and finding a seemingly interminable line of poets young and old who had been coming in buses and trucks since the previous day and now stood in line waiting for their golden moment.

Our group went off for a coffee and roll. By the time we got back to the line it had grown immensely and was now like a snake curving through the city. The poet joined us, proud of his event which he considered a prelude to both the literacy campaign being organized by his brother, but also a harbinger of the fuler development of Mayra’s workshop program. The rules were that each poet could read one poem of his or her own, plus one poem by a poet of choice. It soon became clear that a time limit had to be established because several of the first wave of presenters read an endless concatenation of cantos, all supposedly part of some great epic poem. So we quickly set the time limit. However, as the morning wore on, it was clear people were doing everything to get around the limits. And still the line grew and we knew the poetry marathon would easily go into the next day and maybe more if every one got a chance to read.

“Poeta,” I told Cardenal, “we don’t need a marathon, we need a moratorium on poetic production.”

“Why would we want to do that?” Cardenal asked, making that same pained face he’d given me when I told him I’d chopped up his poems.

“Because the Revolution needs carpenters, bricklayers, construction workers of all kinds, and yes plumbers as well. But if every one’s writing poetry, nothing else will get done.”

“But poets are construction workers building the revolution,” he said. “Poets plumb the depths,” Julio Valle chimed in. “Just like I said,” he added, “This is another Yanqui intervention—but what can you expect from an

‘enemy of humanity.’?”

The literacy campaign began in March, and we helped in some training sessions, but the key event for me in April was a conference meant to organize Nicaragua’s cultural workers in what became the Asociación Sandinista de Trabajadores Culturales. Here participants centered on the question of organizing Nicaraguan artists, writers, and musicians in relation to a projected cultural revolution as an evitable followup to the literacy campaign. My own participation was in a theoretical group led by Sergio Ramírez’s younger brother, Rogelio, a sociologist steeped in Gramscian theory who led us in a heated discussion of how to advance cultural theory in the midst of an “economically retarded society”—how cultural development could help advance a socialist revolution in a country where the more pronounced forms of modern capitalism had not yet emerged.

However it soon became clear that our theoretical debate had little meaning and that the real goal of this meeting was to forge a bloc of artists against what the ASTC organizers, and Rosario Murillo first and foremost among them, considered the populist tendencies of the Ministerio de Cultura. It was the first assault on the Ministerio, aimed at marginalizing Cardenal and putting Rosario in the drivers’ seat. It didn’t seem a serious threat at the time, but it became increasingly important, leading to the dissolution of the Ministry and Cardenal’s displacement as chair of a cultural board supposedly overseeing the Cultural Institute which Rosario herself was to head—one of the building blocks through which she would assert her power in the revolution. My sense coming out of the meeting was that the cultural front like everything else created in those early days, was under attack.

In May it was time for our return to the U.S.; and I ended up some months later on the verge of divorce and coordinating a Latino cultural center at the University of Illinois in Chicago. Sure enough, Cardenal came to the city soon after he’d been reprimanded by Pope John Paul and been expelled from the priesthood for holding a post in the Sandinista Government. I remember our Mayor Harold Washington giving him the key to the city; I remember my department chair kneeling before him and kissing his ring, just as Cardenal had attempted to kiss the ring of the pope, who admonished him in public.

However, as strange as it might seem, what I most remember is when el poeta asked me to take his peasant shirts to the cleaners and I decided that they would d last longer if I had them starched. I will never forget when he got the shirts back and put on one, only to find his sleeves stiff as boards standing out from his arms like angelic wings ready to lift him off the face of the earth.

“But how did this happen? How could you do this?” he asked.

And it was like his torn up poems and my proposed poetry moratorium all over again. As quickly as I could, I dipped the shirt for his presentation into a tub of water, and then squeezed and ironed it until his angelic wings disappeared. But somehow even years later, I could always see them, wonderful, white and maybe flapping in the wind.

My next meeting with Cardenal was at the tenth anniversary of the revolution, where I found myself posing for photos with Cardenal, Galeano and Lawrence Ferlinghetti (I’m sure they were all honored by my presence😅) at the Sandinista book fair, where indeed he told me how he had lost his position as Minister, and how he sensed that the Sandinistas might well lose the upcoming election.

By the time he came again to Chicago, the Sandinistas had indeed lost, and he was no longer a government official. I had already published a new book featuring his poetry and those of his workshop poets, plus a book translating his own insurrection and reconstruction poetry, and a co-written (with John Beverley) a study of Central American revolutionary literature with a large emphasis on his work. He seemed quite pleased by my efforts and asked me to translate and collage-edit materials from his new massive poemario, Cántico Cósmico, for a presentation at a Catholic Church in the city. I pointed out the difficulties I was having with one of his poems which included the line, “me vale verga la muerte.”

“Poeta, I understand what you’re trying to say, but there are going to be several nuns and conservative Catholics at this reading. Are you sure…?”

“Yes he said, “It has to be that.” And it was that. And yes, a few nuns got up and left. Later that night my wife and I and a young Chicano poet went to dinner with him; and after a few drinks, I said, “Poeta, you know why the Sandinistas lost the elections?…”.

“Why?” he dared me to answer.

“Rosario,” I said.

“You’re right!” he all but shouted, now in his cups, “Abuso, puro abuso!”

But surely it was more than abuse, it was the drive for power which possessed perhaps the worst and maybe therefore the most politically ambitious and ruthless of the women poets of Nicaragua… She had successfully humiliated him, virtually taken away his ministry and his job; in the coming years, when the Ortegas came back to power, they did everything they could to belittle and humiliate him.

It is true that at a conference on Central American literature in Granada, Nicaragua, he was very happy to give almost all his attention to a contingent of Puerto Rican literati, including Arturo Echeverría, Mercedes López-Baralt and Luce López-Baralt, especially because the latter had just published a study emphasizing not the political but the mystical dimensions of his Cántico Cósmico (he was so happy to have such a recognition that he seemed to have forgotten the political hack critic who had helped make him popular with the solidarity groups that kept supporting the Ortegas).

What a contrast when he came some years later with his aide, poet Roberto Vargas to present his work at the University of Houston and then at the Rothko Chapell in Houston’s Museum district. He seemed in good humor as he read from his epigramas and salmos, including his Marilyn Monroe poem. But then he scandalized his reverent audience of peace workers and poet-tasters as he contrasted Daniel Ortega with a true revolutionary like Hugo Chávez whom he admired and claimed was also a poet.

As the years rolled on, he continued his alliance with novelist-friend and former Nicaraguan vice president Sergio Ramirez in opposing the distortion of the Sandinista project perpetrated by the Ortegas. As a result, he faced legal problems in relation to a project gone bad in his beloved Solentiname island—a clear case of political persecution for his oppositional stance. In 2015, when Cardenal turned 90, he was feted in Mexico as the Sandinista government had nothing but silence for a man it viewed as a turncoat. In 2012, he received el Premio Iberoamericano de Poesía Reina Sofía, and supported the student uprising against the Ortegas; in 2019, Pope Francis restored his standing as a priest. He died reconciled with his Church, but still firm not only in his opposition to the Ortegas but also in his commitment to revolutionary hope. Three days of mourning were ordered by his nations hypocritical and opportunistic leaders. And word has just arrived of paid hoodlums seeking to maiming his mourning rites, shouting “Traitor” and worse, cursing one of Latin America’s great revolutionary romantics.

One final memory has a special place in my mind. It happened when I met the poet and Roberto Vargas at the Houston airport and drove them into town, unable to stop at a restaurant because their first presentation was to begin within the hour.

“Please!” Cardenal, now in his late 80s, insisted. “I need something to eat.”

“He sounds desperate,” I whispered to Roberto.

“He hasn’t eaten since last evening,” he answered.

I suggested some fast food joint, but Roberto stopped me. “He won’t do that. He needs something good—like a churrasco--or he won’t be able to perform.”

I then put in a quick call to my then and now wife, an incredible Puerto Rican woman from Quebradillas, almost begging her to help out.

“I can quick-heat up some frozen steaks and add some arroz y habichuelas,” she said.

And sure enough when we finally arrived at our house, she served up the steaks, rice and beans, and, as a special touch, some plaintains she’d cooked to perfection—all prepared in some fifteen minutes.

“Umm,” said the poet—thereby uttering the poetic line I most remember from his work.

Apparently, he was a near-vegetarian by conviction, but this dish was what he loved. And now, having fueled up, he was ready to go for his first presentation. We arrived on time.

In our few final contacts, Cardenal always mentioned that meal. But as good as the food was, I’d have to say, he’d fed me and others more than we fed him. Now he is gone, and we will be soon enough. I still remember his starched white cotona with wings.

*Marc Zimmerman

Emeritus Professor at the University of Illinois, Chicago and the University of Houston, Marc Zimmerman worked in Nicaragua’s Ministerio de Cultura in the first year of the Sandinista Revolution. Co-editor of Nicaragua in Revolution, and Nicaragua in Reconstruction and at War, he also edited Ernesto Cardenal’s Vuelos de Victoria/Flights of Victory, and co-wrote Literature and Politics in the Central American Revolutions with John Beverley. He has also written and edited several other books on Central American politics, literature and art, and has recently published a book of memoir fiction, Sandino on the Border, very much related to this essay. Married to Esther Soler of Quebradillas, Puerto Rico, he has taught at the Universidad de Puerto Rico, Río Piedras, and has spent extended periods every year for over thirty years between Quebradillas and San Juan. His book, Defending their Own in the Cold: U.S. Puerto Ricans and their Cultural Turns (2011) will appear in paperback in 2021.

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

PUBLICIDAD 3D