25 de octubre 2023

European Concern over Lack of Academic Freedom in Nicaragua

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

Monseñor Rolando Álvarez, obispo de Matagalpa y administrador apostólico de Estelí. // Foto: Archivo | Confidencial

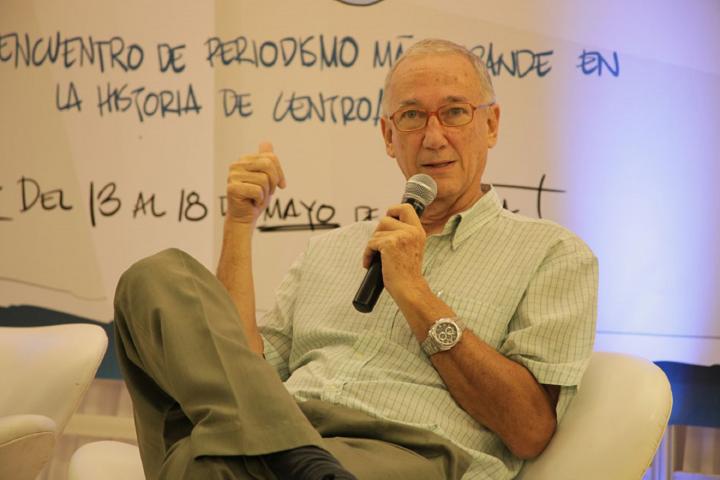

The Jesuit priest Jose Maria Tojeira, former rector of the UCA of El Salvador and spokesman of the Society of Jesus for Nicaragua, considers that the expulsion to the Vatican of 12 Nicaraguan priests who are political prisoners "is symptomatic of the [Ortega-Murillo] dictatorship's weakness," because having priests imprisoned is a constant crisis for a dictatorship that calls itself "Christian and in solidarity." It "is a persistent outcry" denouncing the regime.

In an interview with Esta Semana broadcast –due to television censorship in Nicaragua– on the YouTube channel Confidencial Nica on Sunday, October 23, Tojeira highlighted the "extraordinary example of faith and personal ethics" of the Bishop of Matagalpa, Rolando Alvarez, who is risking his life and health in prison, having been convicted of alleged "treason against the homeland," for criticizing the government's violations of human rights.

Tojeira advocated for the Church to wage a permanent campaign denouncing the "barbaric sentence" against Alvarez and demanding his freedom. He added that to "recognize the value of this man, he should be named a cardinal, which is one of the most important distinctions the Church has."

The Spanish-born Jesuit, nationalized Salvadoran, warned that in Nicaragua, "there is enough awareness among the people, who are being repressed and beaten by the regime, that the power of the dictatorship is eroding," as it loses support among its own supporters.

Jose Maria Tojeira admitted that "it is very difficult to offer an opinion on the future of Nicaragua, because we do not know how long the regime can last," but there is something "that is germinating; there are forces moving internally, although they do not manifest themselves publicly. I do believe that it is real and that the regime has reached a series of contradictions so striking that no matter how much military support it has, it will be difficult to stay in power."

In your article "Nicaragua: Repression and Hope," you describe the repression in the country and also the resistance and hope. Which of these two forces tends to prevail?

When one suffers repression, the most normal thing is to be depressed, but hope also arises, when you see that there are people who resist, when you see that those who leave speak out, that there are still, despite all efforts to shut down freedom of speech and freedom of opinion, people who speak out, who condemn the brutality with which the Ortega-Murillo regime is acting.

So I think we have to have a more optimistic sense of history. That is to say, dictatorships always end up falling. Of course, one would like this one to fall tomorrow, but I believe that there is enough awareness among the Nicaraguan people, even when repressed and beaten by the regime – there is a high enough level of consciousness such that it is eroding the power and even the physical strength of the dictatorship.

First they eliminated electoral competition, political parties, political and civic leadership, non-governmental organizations. But in recent months the repression has been focused against priests and nuns of the Catholic Church and has extended against the parishioners, against the parishes and religious processions. To what do you attribute this offensive against the Catholic Church?

It was perhaps the main remaining sector that, without being as competitive as the political opposition, is still at a level of creating awareness. The Church is a very powerful force and there is diverse thinking within the Church, the opinion of the clergy and the laity. This is a regime that cannot deal with, cannot stand to live with opposition because it is already so close to being beaten by any opposition.

They had to eliminate all political parties in order to win the elections and they want to continue to hold on to power, eliminating any different political thought or any different religious thought, any form of expression that means even the slightest opposition, no matter how small.

We're talking about churches, because they have attacked the Protestants, too. A good number of Protestant pastors –I understand it's up to 60– have also been banished from the country during the last three years. It is the capacity to create awareness that churches have that has provoked this final effort of a dictatorship that is already, I believe, in its last days, because it has less and less support. It is a dictatorship that needs to eliminate all political opposition in order to remain. It is a dictatorship that will disappear relatively soon.

This Thursday the regime released and banished 12 priests who were political prisoners. Some of them had already been sentenced, others had been recently arrested. In Rome, the Vatican said it would receive them, but that there was no negotiation. There is no change in the police state, which continues to act against Nicaraguan citizens and the Catholic Church. What does this release mean?

It is symptomatic of the dictatorship's weakness. To have priests imprisoned is a constant crisis for a dictatorship that talks about being Christian, socialist, in solidarity.

They themselves said, in the statement they issued, that "out of respect for the Catholic Church we are releasing them." It is not out of respect; it is because having them imprisoned is a persistent outcry.

So, if he is the one who has decided to stay –Monsignor Alvarez–, it seems to me that he is making a very important statement because his silent, isolated imprisonment is a permanent international outcry about the brutality of the dictatorship. I believe that he is doing more damage to the dictatorship being imprisoned, silent and silenced, than when he was free to speak out against the dictatorship.

The priests have been released because of that and they [the Ortega regime] are upset that the bishop doesn't want to leave the country. I think it's a significant statement, both from his faith and his personal ethical option, which is so important to raise awareness of what is happening in the country.

How is Monsignor Alvarez's example being seen? He is sentenced to 26 years in prison for fabricated crimes that he never committed. He has been a finalist for the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought with Dr. Vilma Núñez de Escorcia and he demands his unconditional freedom. Pope Francis himself has said he respects his example of faith.

For me Alvarez is a tremendous example of faith. His silence is more powerful than his voice. At some point I have said that if the Church wanted to do something to recognize the value of this man, they should make him a cardinal, which is one of the most important distinctions the Church has. And an act of trust in a man who is risking his health. In the face of such an unjust decision of the dictatorship, he is risking his own life and his own health, both physical and psychological.

I believe that the Church must recognize him, insist on the issue, he must be free. A person who is sentenced to 26 years for "treason" – what does that mean? It's understandable that in a war there can be treason, passing official secrets to the enemy, but just for saying that this government commits violations of human rights, can that be treason? Who does the government think it is? They confuse government with homeland. It is so absurd what they have done to him, that it's impossible to know how to react. But yes, his example is extraordinary.

In the face of this imprisonment of Monsignor Alvarez, the Catholic Church in Nicaragua –or at least the Episcopal Conference– remains silent. They say it's for fear of reprisals. Some priests who have invoked his name in their parishes were among those arrested in recent weeks. How do you assess the international reaction of the churches, the Vatican and the international community?

There have been some important statements by episcopal conferences in Europe and Latin America in defense of Monsignor Alvarez. That is undoubtedly important. But I believe that this type of condemnation of his imprisonment should be more constant. It is not enough to say that what the Sandinistas have done to this bishop is bad. The outcry has to be repeated continuously, because he is still there. And really within the framework of human rights it is said that disappearances are ongoing crimes until the appearance, dead or alive, of the person. Monsignor Alvarez is not disappeared, but an unjust imprisonment is an ongoing crime, and it has to be denounced in an ongoing way. It is like the issue of the disappeared: we cannot let it go, we must continue to insist. He has a barbarically unjust sentence, because 26 years for nothing; it is crazy, legally speaking. So one says, well, we cannot forget this and we cannot keep quiet about it. And I think it's important that important structures of the Church, such as episcopal conferences, or bishops who have public status, speak out frequently. That is very important.

This article was originally published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by our staff.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense, exiliado en Costa Rica. Fundador y director de Confidencial y Esta Semana. Miembro del Consejo Rector de la Fundación Gabo. Ha sido Knight Fellow en la Universidad de Stanford (1997-1998) y profesor visitante en la Maestría de Periodismo de la Universidad de Berkeley, California (1998-1999). En mayo 2009, obtuvo el Premio a la Libertad de Expresión en Iberoamérica, de Casa América Cataluña (España). En octubre de 2010 recibió el Premio Maria Moors Cabot de la Escuela de Periodismo de la Universidad de Columbia en Nueva York. En 2021 obtuvo el Premio Ortega y Gasset por su trayectoria periodística.

PUBLICIDAD 3D