17 de octubre 2023

European Concern over Lack of Academic Freedom in Nicaragua

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

Edgar Gutierrez, Guatemala’s former foreign minister believes Bernardo Arevalo’s election is legitimate, but it’s been caught “in the crossfire”

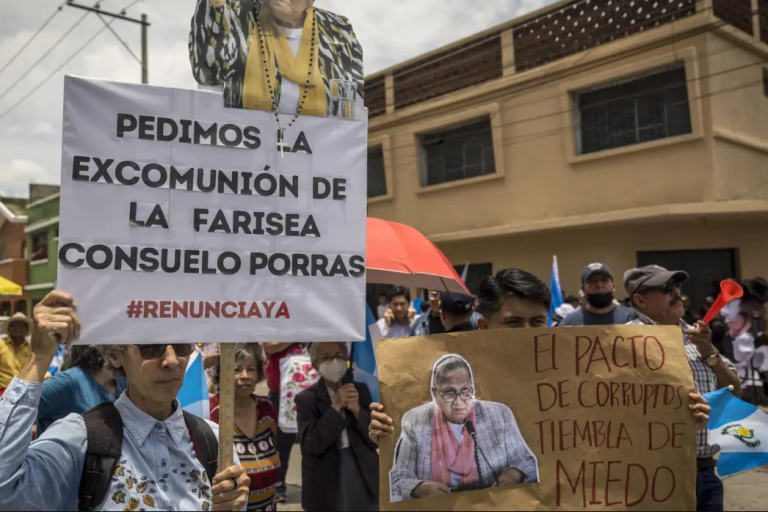

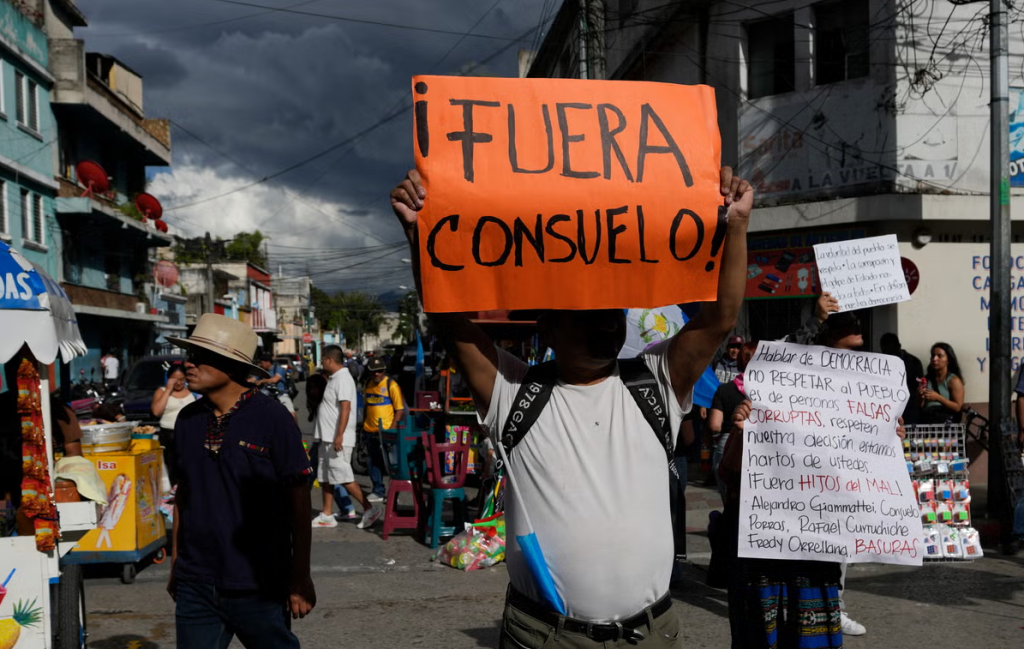

Following two weeks of citizen strikes, with highways blocked and protesters demanding the departure of Consuelo Porras, and respect for the popular will that elected Bernardo Arevalo to the presidency on August 20th, “Guatemala faces a delicate political balance,” declares former foreign minister Edgar Gutierrez, now exiled in Mexico.

On the one hand, the citizens’ movement – led by the mayors of the indigenous towns – has succeeded in paralyzing the country. On the other, President Alejandro Giammattei and the private sector are refusing to pressure Attorney General Porras into resigning. Instead, the current president has endorsed Porras’ efforts to derail the popular mandate given to president-elect Bernardo Arevalo.

If the next weeks don’t bring a violent outcome to the protests, or a negotiation, and the impasse continues until Bernardo Arevalo’s scheduled inauguration on January 14 of next year, “Arevalo will succeed in becoming Guatemala’s next President, but amid great wear and tear and with a very precarious capacity to govern,” Gutierrez warns. The conversation between Confidencial director Carlos Fernandez Chamorro and the former Guatemalan foreign minister took place on the weekly online Nicaraguan news program Esta Semana.

Right now in Guatemala, there’s a President-elect -Bernardo Arevalo- who won the elections. But there also seems to be a Coup d’etat in progress, spearheaded by the Attorney General and aimed at keeping Arevalo from taking office on January 14. Which way is the political balance tipping?

Edgar Gutierrez: It’s a very delicate balance. The mobilization of the indigenous peoples has been well established. It’s been going on for nearly two weeks now and has paralyzed the country. This movement of the indigenous people, led by their ancestral authorities, is very important, but it’s not about the defense of Bernardo Arevalo of the Semilla Party – it’s a matter of defending the integrity of the vote, and enforcing respect for the popular will that was expressed at the polls last August 20th. And this has leveled the playing field.

Clearly, the Attorney General’s office has the force of the criminal accusation behind it, but it also has the enormous weakness of illegality and lack of legitimacy. In fact, in the last three or four days, Attorney General Consuelo Porras hasn’t appeared in her office, and is apparently spending her nights in the army barracks. That image is evidence that they’re all but cornered by the people.

However, Consuelo Porras has declared she’s not going to resign, and President Giammattei has said that he can’t dismiss her because, according to the law, she’d have to be guilty of some crime for that to happen. So, will Attorney General Consuelo Porras, Prosecutor Roberto Curruchiche, and Judge Orellana all remain in their posts?

To be found guilty of a crime, she would have to judge herself or present such a case, and she’s not about to commit legal suicide. The President has other instruments. For example, he’s the head of the State bureaucracy, and he could apply an administrative sanction because she hasn’t shown up at her office for three or four days, and has no formal excuse not to do so.

President-elect Bernardo Arevalo has accused President Giammatei of being the one responsible for this crisis and has demanded he take action. But what’s Giammatei’s position? Is he endorsing or questioning the attitude of the Attorney General’s office?

He’s endorsing it. If President Giammatei thought at any time about removing his support for Attorney General Consuelo Porras, that moment expired on Monday, October 9th, when the Attorney General put out a statement on social media in which she all but threatened to take the President to court if he didn’t stop the popular demonstrations.

That same Monday, the President also appeared on television, in a nationally synchronized broadcast, affirming that he was going to stop the demonstrations. So, here’s a game of blackmail in which the Attorney General claims to have some buried court cases against the President, and – out of fear – the President responds through the media, essentially implementing her orders.

In terms of the citizen protest movement you mentioned a moment ago – What are its dimensions in terms of the national territory? Some people are complaining that the protests are interrupting the normal flow of business and services, and are demanding that the authorities put an end to the roadblocks.

The demonstrations have a national scope. There’ve been days in which over 200 points have been closed by demonstrations and blockades. Most of them have been barricades across highways or roads.

The Constitutional Court has declared that the blockades are illegal, but that the marches and demonstrations are legal. So, what people have done is a mix, a hybrid, between blockades and marches, allowing ambulances and services that meet basic needs to pass through. But yes, it has strongly impacted the private sector, especially the group that exports vegetables and other perishable goods. They’ve suffered large losses.

What’s the position of the large economic powers, the company owners grouped in CACIF [“Coordinator of Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial and Financial Associations”] in this crisis? Between the Attorney General’s position questioning the electoral mandate, and the citizen protests these actions have provoked, where do they stand?

[Their response has been] silence, omission, and help for Consuelo Porras and her plans. In this delicate balance I referred to in the beginning, a conclusive stance on the part of the private sector could tip the balance in favor of the democratic forces. But they haven’t done so, even though a part of this sector is suffering losses. The Attorney General’s game of blackmail has extended into one part of the private sector as well, and for that reason they’re afraid to make any pronouncement.

Fear of blackmail in the form of accusations from the Attorney General’s office?

[Yes], of having the Prosecutors renew cases that have been filed away for years, regarding the involvement of one part of the private sector in illicit electoral financing. That’s one of the areas where the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) filed cases five years ago.

The Constitutional Court, which is supposed to be the great legal and political arbitrator of all these disputes in Guatemala, has practically given the Attorney General’s office a free hand to continue with its persecution of the Semilla Movement – the party that won the elections and underwrote the President-elect. Is there any means of appeal?

There’s no appeals body. Legally, after a ruling from the Constitutional Cout, there isn’t any appeal. The Magistrates on this court have the last word, and their resolutions, as the Constitution itself states, are final. But it can also change its opinion. Up until now, the Court has thrown out the appeals presented by very respected lawyers, arguing that applying the law against organized crime – the law the Attorney General’s office has invoked against the Semilla Movement and President-elect Bernardo Arevalo – is very dangerous. The same law they’re applying against a political party today, could be used tomorrow against a large company or against any common citizen. And this legal discussion still hasn’t taken place, but it needs to happen, because the accusation the Prosecution is presenting against the Semilla party and Bernardo Arevalo is disproportionate.

Meanwhile, there’s an agreed-upon government transition process between outgoing President Giammattei and President-elect Bernardo Arevalo, monitored and accompanied by the Organization of American States. Is this transition process currently in progress, or is it paralyzed?

Formally, it has continued, after being paralyzed for a few days. But the contents of this transition are practically nil. What’s taking place are mere formalities, and the OAS mission that has remained and will stay on until January 14, are taking care not to let the process fall apart. Instead, they recently oriented their participation towards mediating between the demonstrators and the government. A few days ago, there was a meeting between the ancestral indigenous authorities and the President, but they weren’t able to come to any agreement. Hence, the spotlights are more concentrated on the demonstrations, on the blockades than on the transition process itself.

What weight does the legitimacy of President-elect Bernardo Arevalo have, considering his electoral victory and his relationship with the different political, social and economic forces in Guatemala? At the end of the day, isn’t that issue what’s at play in this crisis?

Outside of the Attorney General’s office and another very radical group, no one questions the electoral results. The President-elect has full legitimacy. But the bursting in of the indigenous movements have overshadowed that a little, and Arevalo himself been lost in the crossfire. On the one hand, conservative sectors have accused him of instigating the national strike; while on the other, the indigenous and grass-roots social movements say: “We’re not here for the President-elect – we’re here defending the vote and defending democracy.”

As a result, Bernardo Arevalo has been left somewhat on the defensive, because he’s not the one leading the protest movements. Yes, of course, he supports them, but it’s also not him pushing the forces towards illegal acts. So, Bernardo Arevalo himself is in a slightly awkward position at this juncture.

Can this situation continue indefinitely in this state, right up to the transfer of power on January 14th, or is there a risk of its ending in violence, or perhaps in some kind of negotiations?

Up until now, the first attempt at negotiation didn’t function. Also, we should recognize that the security forces, the Police, have behaved in a very correct manner, and haven’t engaged in repression, which seemed the principal risk when all this began. There’s been a lot of dialogue and understanding with them.

However, we’ve begun to observe the organization of groups we could call “white guards” – some extremist groups, some wealthy groups, with their guards, with dozens of bodyguards that are beginning to get organized and want to break the blockades and break up the demonstrations in a violent manner. Up until today, there haven’t been any confrontations, but yes, it’s a latent risk that such clashes among civil groups could be produced. And these armed “white guards” could end up generating victims, which – luckily – is something we haven’t seen in these last two weeks.

If this delicate balance is prolonged, and the moment to transfer power arrives, would Bernardo Arevalo have the governing conditions to exercise his electoral mandate? Or would he end up being a president under constant siege and threat?

The President-elect has suffered tremendous wear and tear during these weeks. The objective of the social protest movements is to force recognition of the Semilla Movement’s victory and the elected president. If this continues until mid-January, they will have achieved their objective, in the sense that Bernardo Arevalo will be assuming the Presidency. But these are very exhausting conditions for him, leaving a precarious and fragile democratic governance. He’s going to be called upon to govern amid some very complicated scenarios.

This article was originally published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by Havana Times.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense, exiliado en Costa Rica. Fundador y director de Confidencial y Esta Semana. Miembro del Consejo Rector de la Fundación Gabo. Ha sido Knight Fellow en la Universidad de Stanford (1997-1998) y profesor visitante en la Maestría de Periodismo de la Universidad de Berkeley, California (1998-1999). En mayo 2009, obtuvo el Premio a la Libertad de Expresión en Iberoamérica, de Casa América Cataluña (España). En octubre de 2010 recibió el Premio Maria Moors Cabot de la Escuela de Periodismo de la Universidad de Columbia en Nueva York. En 2021 obtuvo el Premio Ortega y Gasset por su trayectoria periodística.

PUBLICIDAD 3D