29 de mayo 2018

European Concern over Lack of Academic Freedom in Nicaragua

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

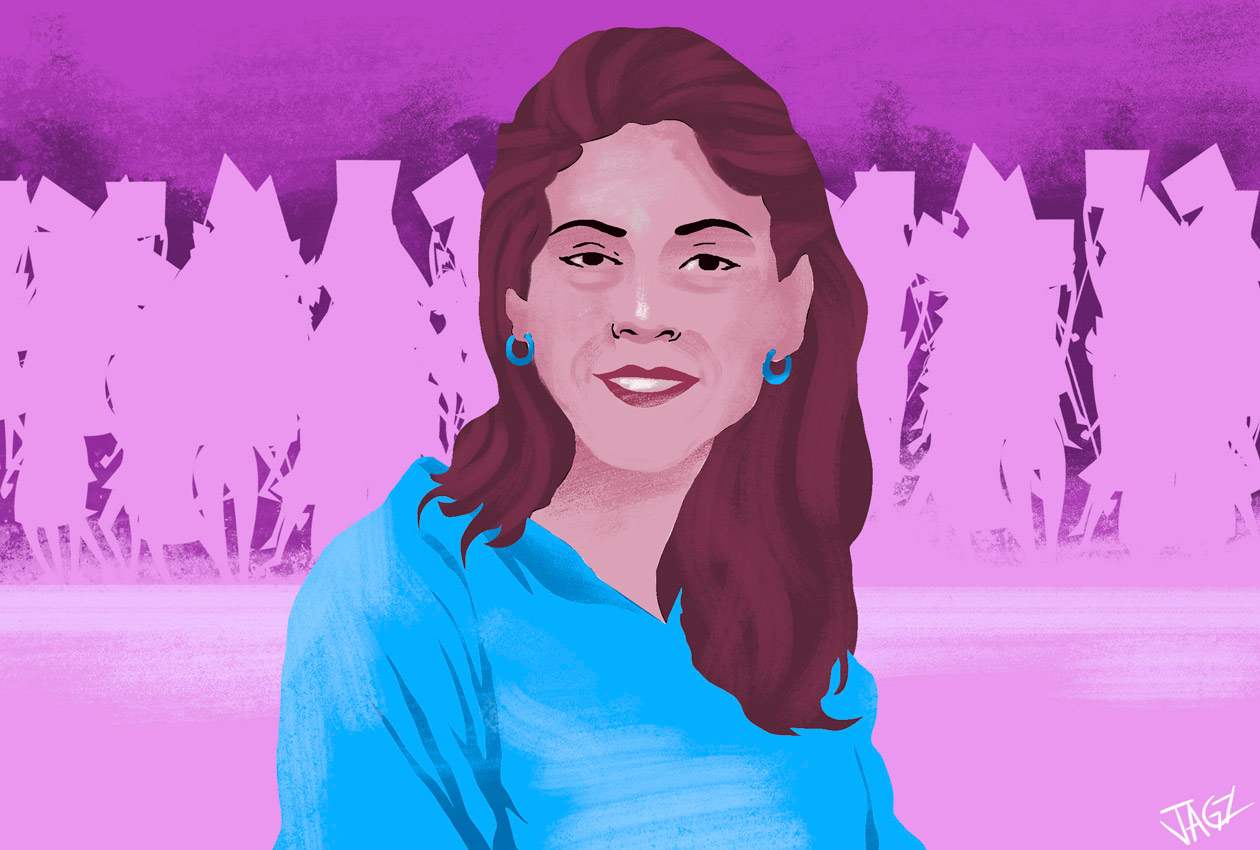

“Whoever says there are no women in this struggle doesn’t know anything.”

Illustration: Juan Garcia

“We won’t act until Pancha gives the word!” is heard in the area around Gate 5 of the Nicaraguan Autonomous National University (UNAN) in Managua. There are people waiting to get into the campus, but the gates are still closed. She’s a few meters away, supervising other activities that “her muchachos [guys]” are carrying out. That’s what she calls the students from her squadron behind the barricades in this occupied university. Someone informs her of the request, she okays it, and the gates are opened almost immediately. In her area, no one hesitates when she gives an order.

“La Pancha” is very thin and a bit under 5 feet tall, with a soft voice. However, as her classmates affirm, she’s a figure that represents trustworthy horizontal leadership. Together with more than 500 students, she’s been occupying the UNAN campus since May 7. “It’s been hard,” she admits.

Ilustración: Juan García

In the UNAN, everyone uses a pseudonym. Hers emerged because it’s related to her real name. Many don’t know what this real name is, though, and she prefers it that way. “I don’t want to face reprisals for demanding justice,” she says. “Pancha! Pancha!” is heard every ten minutes or so from her companions asking her about new duties. She merely signals with her hand that they should ask her later. They stop insisting.

The young peoples’ demands are clear: in addition to rejecting the National Union of Nicaraguan Students (government-affiliated student union), they are fighting for the democratization of the entire country. “We want to be the example, we want a free and sovereign Nicaragua,” they affirm.

Within the campus are more than 200 women. Most of them sleep there on the premises. “We all manage to accommodate ourselves here,” she says.

To Pancha, in her university, at her gate, no one sees gender. “We’re not going around concerned about whether you’re a man or a woman. We’ve been caught in crossfire together without that being an issue at all. There’s a general respect, as there has to be,” she notes.

Her “guys” trust her decisions, both inside and outside of the conflict zone. She’s the leading voice of “Area 5” and her opinions carry a lot of weight within the meetings of the section heads. But she doesn’t like to be “authoritarian”. “I try to ask how the others feel, how something might affect my compatriots,” she explains.

Pancha wears jogging pants with a tank top and Crocs on her feet. She likes to wear eye makeup, since it’s the only part of her face that’s visible when they take photos. For her “being feminine” isn’t a synonym for weakness. Without hesitation, she affirms that in the university “the girls are strong” and she’s a witness to that.

There are cooks, those keeping watch, handling the homemade mortars, making the Molotov cocktails, psychologists and leaders like her. “Whoever says there aren’t any women in this struggle doesn’t know anything,” the student declares.

Yartza moves confidently with a penetrating gaze. Her objective is “to free the people from dictatorship and organize the UNAN.” A little over a month ago, Yaritza was focused on finishing her Political Sciences career in the same place where she now sleeps and battles. “This has all been hard,” she admits.

She’s participated in the protests since April 19, and has been occupying the building since May 7th. She was also in the protests at the Engineering University and in the assault at the Managua Cathedral where she thought she would die.

Ilustración: Juan García

Today she looks tired. Between organizing and defending themselves, the days pass “incredibly quickly”. Daily she crosses the hallways where Arlen Siu also walked when she was studying psychology. Arlen, a female guerrilla fighter in the struggle against Somoza, has become an inspiring figure to many women in the protests.

In April, Yaritza joined the University Coordinating Group for Democracy, the student group that formed part of the National Dialogue. However, she didn’t attend these sessions that were suspended on May 23. “We were in danger, and I felt that being there wasn’t as important as helping my companions here (in the UNAN), she states.

Together with other students, she attends daily sessions to discuss the current context of events. She offers her opinion without thinking twice about it: “to make change” all sectors of society need to be taken into account. If she’s not heard, she repeats what she thinks, with a louder and firmer voice.

“This isn’t really new, but I’ve noticed that there are men who repeat exactly what some woman just said, and they DO get listened to. The strongest voice doesn’t mean the greatest intellect,” she says.

But Yaritza tries not to focus on that, but on organizing at her university and on the physical protection of her companions there. One of her greatest fears is of being “misinterpreted”. I’m not interested in a political post, but I understand that the National Union of Nicaraguan Students has left us traumatized about this. I only want to offer support however I can,” she says.

Since the protests began, she tells us, she’s learned first aid, taught by the medical students. “I’ve heard horrible stories,” Yaritza assures us. Stories like those of “Dr. Ramirez”, a fifth-year medical student in the UNAN.

“Dr.” Ramirez spent the whole day on April 20 attending to young people who were wounded in the protests at the Engineering University (UNI). It was one of the darkest days of her life. Her “office” was in an empty lot between the Cathedral and the University Hall, and by five in the afternoon she had already seen a student with a bullet through the head. She had to hold back the tears and go on helping. That’s what they had taught her at the University.

Ilustración: Juan García

Every ten minutes, someone else arrived needing help, the majority with bullet wounds. Among all the blood, she received a student with a wound between the mouth and the throat. He was short and thin and identified himself as Alvaro Conrado. “I could only help him for a few seconds; his voice and his gaze were something that I can never forget,” she recalls sadly.

Alvaro was only 15, and they all could see that he wasn’t a university student. He couldn’t talk well, but he kept trying. They’d shot him in the face and neck. She held him up until someone else arrived to assist her. “Alvarito’s” blood stained her hands and her clothes. “I wished for him to live, I wished that the bullets hadn’t harmed him.” He died that same day.

What happened in that month of April took her by surprise. “I never thought I would see students die at the hands of the police, or see our fellow Nicaraguans killing them.”

“The struggle belongs to all of us,” she underlines. She recalls that in the medical outposts everybody helped everybody else without regard to gender. “Women and men had the courage to be up front in the barricades, responding to the attacks with rocks and homemade mortars, or taking on similar roles helping the wounded or those affected by the tear gas. Women and men helped out in getting a plate of food to those at the barricades, we were all equals,” she explains.

Nobody from her family knows that she was in the Cathedral and her family wouldn’t want her to be helping inside the universities. “They’re afraid,” she tells us. She’s scared too. Since April 19, when she took up her medical instruments, she knew she was risking possible reprisals. “My future or my life could be affected, just because I helped,” she states.

Even so, she continues by the barricades and won’t stop doing so until she can see Nicaragua freed.

Ivette Munguia was hidden behind the trunk of a tree, near the Nicaraguan Polytechnic University (Upoli) when she saw the lead bullets fly by shot by the National Police. She thought about death. In her last attempt to flee, she was intercepted by several members of the riot squad. She was in shock.

Ilustración: Juan García

That April 21, her assignment was to cover the student protests in the Upoli. When the police captured her, Ivette had been in the area of the University for more than six hours.

The police were attacking the demonstrators. While they put her in a judo hold on the floor, she could see how they formed groups of five to beat the other young people. She didn’t know what to do, but managed to yell, “I’m a journalist!” Before stopping the violence, they took away her ID cards and her cell phone, then they let her go.

“Get out of here!” one of the policemen yelled at her. She couldn’t respond. They hit her and repeated – “Just get out!” She raised her hands and ran to a secure place.

The day before, the reporter had been locked into the Managua Cathedral. “In the field, you forget that we’re all human and exposed to risk,” she says.

Although Ivette has seen several of the young people die in the protests, for her the most traumatic thing was attending their funerals. “To see the mothers crying, screaming by the caskets is something that is still very fresh in my mind.” She can’t get over it.

Her voice has accompanied the live broadcasts of the newspaper La Prensa, seen by thousands of people. “At times we put ourselves out there to get a striking image. Our labor is to bring the truth,” she explains.

The majority of the newspaper’s reporters are women. Like her, her colleagues have put themselves in very high-risk situations: during the Monimbo rebellion, inside the Cathedral, in the crossfire in the universities. “Being a woman hasn’t been an impediment for carrying out our work in a professional manner, and for doing the best we can,” she comments.

The protests have caused her to mature, and she’ll continue going out on the street, notwithstanding the risk. “That’s our mission,” she concludes.

Madilaine Caracas’ yell has become familiar in Nicaragua. Leading the protest for the wildfire at the Indio Maiz reserve; telling off Edwin Castro, a parliamentary deputy and law professor at the Central American University; facing down Daniel Ortega at the National Dialogue with a list of those killed; her demands are always loud and clear.

Ilustración: Juan García

“Ferocious” is a good adjective to describe her. Her social conscience comes from her background for the feminist cause. When she speaks, she knows what she has to say and doesn’t hesitate to say it. She’s become one of the symbols of the struggle.

Months previously, she would use her paintbrushes to illustrate some of society’s problems, such as harassment in the street, mental health and domestic violence. Madelaine gave up painting to dedicate herself to changing Nicaragua. But the change won’t happen without a restructuring of our collective thinking, she affirms. For her, “Free Nicaragua”, also means a Nicaragua without racism, machismo or classism.

Madelaine is still a student, but her fight is against the regime. For that reason, she can’t stop criticizing the models of machismo she sees in their own spaces. She doesn’t forget that someone once once told her: ‘the women should keep struggling from below while the men show their faces to indicate more power.” “That broke my heart,” she relates.

Her name is already part of the history of Nicaragua. In the social networks, she’s seen as an icon, a feminist, a university student and an activist. Nevertheless, she expresses, this is a double-edged sword. Madelaine’s received threats of rape and murder on the internet, as have other young women in the struggle.

“We get really macho comments. They make me into an object. It’s a lot easier to take down a woman, because people focus on things that they wouldn’t talk about with a man,” she notes sadly.

She’s a valiant warrior who demands space for other excluded groups. With a firm voice, she says: “We have to reinvent ourselves, and one of the cornerstones of this has to be the participation of women. But not only of women.” For this student, the representation of the farmers, the indigenous communities and the descendants of the Africans is also vital. These groups, she emphasizes, experience totally different realities and need to be heard.

“We can’t continue to replicate authoritarian models,” she states. For that reason, she thinks that feminism needs to be discussed in these moments. She’s convinced that replicating today’s machismo will condemn Nicaragua to more failure.

In other words, “Flower of one night” as she’s also known, is fighting for freedom. “You have to bring up uncomfortable topics,” she insists. She’s fighting for her own freedom, for that of the country and for that of the women who inhabit it. “We need to create the concept of a country where there’s justice,” she concludes. When she speaks of justice, it’s for all.

*****

“Listen, companero, the truth is that you can’t make a revolution without women’s participation,” comes from the speaker during a protest in Nicaragua. The demonstrators yell and get ready to sing. The phrase is the opening to a well-known song: “El Zenzontle pregunta por Arlen” [“The mockingbird asks about Arlen”] which spoke of the feminist participation in the Sandinista insurrection and has gained new validity within the current context.

In the Dialogue, in the medical centers and in the trenches, there are women, too. Anonymous faces that have contributed essential work to the struggle. On the walls of the country appears the slogan: “The revolution will be feminist or it won’t be at all.” If there’s one thing all agree on, it’s that this phrase isn’t about separating but tries to be inclusive. Many others say: “the struggle belongs to all of us.” Once again, the views coincide.

Translated by Havana Times

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

PUBLICIDAD 3D