31 de mayo 2023

Ortega Grants Chinese Company a Huge Mining Concession

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

* "Ambitious politicians in Latin America are not looking at Ortega or Venezuela, they're looking at Bukele as their model to copy."

El presidente de El Salvador, Nayib Bukele. // Foto: Archivo

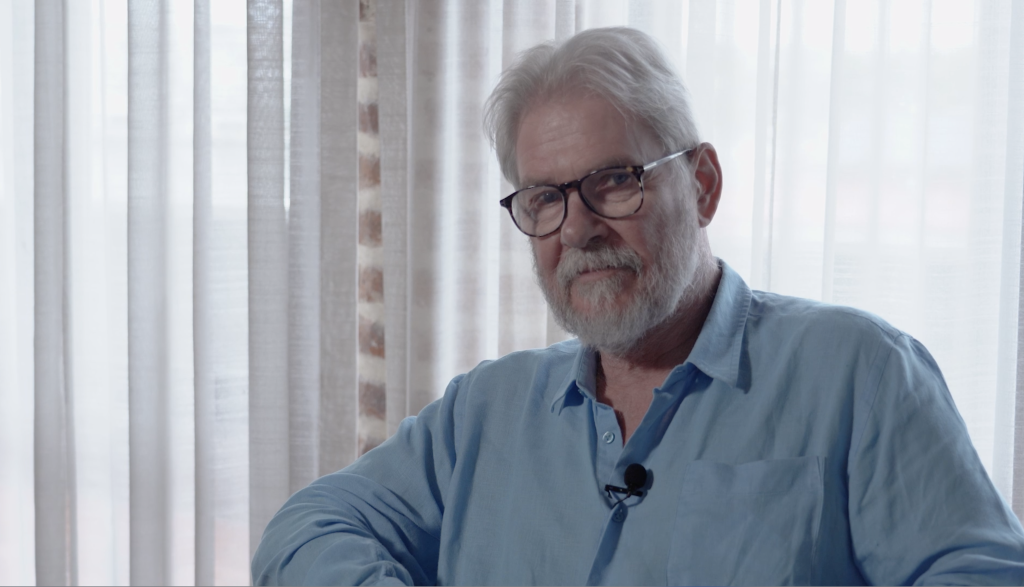

Latin America, the forgotten continent is the title of the important political, economic, and social chronicle by the British journalist and writer Michael Reid. Published more than a decade ago, it is subtitled "the history of the new Latin America" and "the battle for the soul of Latin America", and at the time it was received as the counterpart of The open veins of Latin America by the Uruguayan Eduardo Galeano, published in 1971.

The book by the former correspondent in several Latin American countries for The Economist, who was also senior editor for the region and author of the specialized column Bello between 2014 and 2023, is a critical analysis of the political and economic reforms in Latin America at the beginning of the 21st century. It focuses on the debate between populism and democracy and offers a predominantly optimistic vision. In the second edition of the book, Reid modified this view, with warnings about clouds of stagnation and authoritarianism.

Recently retired from the editorial staff of The Economist, Reid published a new book, Spain: The trials and triumph of a modern European country, this past April, but he continues to exercise his expertise as a keen observer of the Latin American region. Last week he spoke in the Dominican Republic at the tenth edition of the literary festival Cuenta Centroamérica. During a break, Reid spoke with Esta Semana and CONFIDENCIAL about the challenges facing the new governments of Chile, Colombia, and Brazil; the dialogue between the European Union and Latin America in which "neither side is listening to the other"; the economic presence of China in the region where the United States has left a vacuum; and the dictatorships of Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua "The model for the new authoritarian tendencies in the region is not Ortega or Venezuela", says the British writer, but "Nayib Bukele, who has revealed himself as an elected and effective autocrat in the short term. That is their model to copy."

Your book, Latin America, the Forgotten Continent offered some optimistic trends about Latin America when it was published fifteen years ago. How do you see the continent today?

Yes, it's true. In the second edition that was published in 2017 in English and in 2018 in Spanish, I was less optimistic. There are some warnings of more negative trends.

I think there have been important setbacks. If one looks at the region as a whole, there are already three open dictatorships: Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua. El Salvador is on that path. And in Guatemala it seems to me that everything indicates that the next election is not going to be a free election. Beyond that, there is a very difficult situation in terms of the combination of economic stagnation in many countries, with much social frustration, and the emergence or resurgence of populisms with authoritarian tendencies in some cases.

How do you see the beginnings of the governments of the new democratic left in Latin America: Boric in Chile, Petro in Colombia, and Lula in Brazil? Let's start with Boric and the recent vote for the new Constitution.

Let me start by saying that this current wave towards the left is weaker than the previous one, because in large part they won because people are fed up with the situation and with their governments, more than for ideological reasons. Also, there is more variety among them. Jorge Castañeda, the former Mexican Foreign Minister, said about the first wave of the left that there were two lefts. I think that now there are more.

Boric is a democrat who believes in human rights, and that is very important. That said, he came to power too young, I think. He came to power because of the circumstances, because of the social unrest in Chile. It was in an election where the vote was not obligatory, and he came linked to another utopian left. He seems to be a much more pragmatic person who is learning, but he is learning through mistakes. So, it is a government whose destiny was linked to the Constitution project, which was rejected. It was a very utopian project and not viable for Chile, and it was overwhelmingly rejected by the voters. That has inevitably weakened the government. And this month's election of the new Constituent Council is also a victory for the right, mainly for the hard right.

Boric has a program whose central elements are praiseworthy–to pass a tax reform to strengthen the welfare state in Chile and to invest more in human capital, which Chile needs. The concern now, which is the opposite of what there was with the draft of the Constitution of the left, is that the right will try to block or immobilize any change that in the medium term is going to sow, or could sow, the seeds of another explosion.

Petro has just announced the end of the coalition government and says that now they are going to promote revolutionary changes in Colombia. Is Petro's project at all viable?

I don't think so. President Petro is a very complex character psychologically. On the one hand, he is this utopian, populist, nationalist revolutionary whose formative experience was his years as political operator of the M-19, of the nationalist guerrilla. Then there is another, more pragmatic Petro who decided to form a broad coalition to govern at the beginning of his term.

In the face of frustrations –and this also happened when he was mayor of Bogota– he threw out his toys, he threw the technocrats of the center-left out of the cabinet, and he's now governing with activists.

There is no majority in the Colombian Congress nor in the population, that backs the kind of fundamentalism of his electoral program. He was not elected because of his electoral program, he was elected because his opponent was unacceptable and because there is a sector of the population that wants change. But a good government leader is someone who recognizes that he cannot do everything all at once. Now, if he decides to govern from the balconies, "mobilizing the masses" so to speak, it could be very destructive, and I do not think he will be successful.

Lula faces a polarized, divided country, with great environmental challenges. It seems that he is focusing his priorities on his foreign policy, on the issue of the war in Ukraine.

Yes, I think it was very important for Brazilian democracy that Lula won. But he won –and it's a bit like Colombia in that sense– because a sector of centrist voters thought Lula was preferable to Bolsonaro. He could have done much more to represent those sectors in his government. He has given space to right-wing sectors in Congress because he needs their votes, but he is still very attached to his party, the Workers' Party, which has never criticized or even acknowledged its own corruption or Dilma Rousseff's disastrous economic policy.

This puts Lula in a weak position. His margin of economic maneuvering is small. As you say, it seems he is going to spend quite a lot of energy on foreign policy, but it's going to be more difficult than last time, because last time he could be an important figure in the world because he had a very strong domestic position, and there was domestic political stability.

This time, the area where he can make a difference is in environmental policy. The world is going to look at this very positively, as he is doing much more to preserve the Amazon. But I think that his attempt to position himself as a mediator in Ukraine didn't go well, because instead of adopting a neutral position, he adopted a position much closer to Russia, which is difficult to understand.

Does Latin America have a common position vis-à-vis the European Union, for example, given there's a summit coming up in June? Or vis-à-vis the Biden Administration in the United States? Or is it not a unified position because of the different agendas among the countries?

I think there are different agendas. The Spanish government has substantially raised expectations for this summit. It is going to be difficult for there to be concrete achievements; or rather, the achievement would be that they manage to meet after eight years. These summits were supposed to be biennial. The concrete project that could come out of this is the European Union-Mercosur cooperation and trade agreement, which began to be negotiated 24 years ago. The negotiation was completed three or four years ago, but it has not yet been ratified. Lula says he wants to renegotiate it. It's going to die, because there are governments in Europe, such as France, Ireland, and Austria, who want nothing to do with this because they are protectionist in agricultural matters.

So, the summit will be dominated by that and by Ukraine. And in terms of Ukraine there are very big differences because there is, with some reason, a feeling in Latin America that "it's not our war". Obviously for Europe, for the democratic cause in the world, "it is our war".

There are also many Latin American countries that don't want to take sides for the West against China. They don't want to have to choose, because they have important economic interests with China, and because they perceive the West's positions to have been somewhat hypocritical in terms of their proclamation of a liberal international order. So I think there's going to be a dialogue in which neither side is listening to the other.

It's true there is a growing Chinese presence, especially economically, in Latin America, filling a space and a vacuum left by the United States.

Indeed. There is no doubt that today's world is much more multipolar than the world of 20 years ago. In relative terms, China has emerged, and not only China, but India, Turkey, some Persian Gulf countries. And on the other hand, in relative terms, Europe and the United States are less powerful than they were.

So it is logical that Latin America has much more relations with China and India than it had before, and it's because of that empty space. But we have to remember –I remember because I covered the negotiations for the Free Trade Agreement between the United States and Latin America, which was a project 25 years ago– that it was finally Latin America that said "No, we do not want this." So, it is true that it is difficult to imagine that the U.S. Congress would approve it.

So who left that space empty? It's true that the U.S. agenda in Latin America is totally dominated by domestic concerns, political concerns, migration, drug trafficking and organized crime. And China does not have those concerns, but what does China have to offer in the long run? China is complicit in a relative "reprimarization" of the economies of Brazil and Argentina, for example. China offers credits, but its conditions are tougher than those of the World Bank or the Monetary Fund. And will China at some point demand a diplomatic quid pro quo? We shall see.

There's also a contradiction. While Latin America has economic interests with China, I think there is no doubt that the Latin American population feels that their values are more aligned with those of the United States and Europe than those of China. What Latin American wants to migrate to China? I have met some Brazilian entrepreneurs in the shoe industry in Guangdong but only a few.

The three dictatorships you mentioned, Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua – what weight do they have today in the region as a whole? What had been Chavez's project, ALBA [Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America] project, has been reduced to a Venezuela that no longer has that kind of economic power.

I think that surprisingly this group has some weight, especially Cuba and Venezuela, because they have political allies in many countries. There is strangely still a nostalgia for the Cuban revolution and Fidel Castro, and for Hugo Chávez. Although all the evidence shows that they are countries that are basically prisons and economic failures.

You do not have to believe in conspiracy theories to see, for example, that there's a presence of Cuban intelligence in several countries of the region. Another aspect is that many leaders of the Latin American left don't necessarily want to copy these projects because they recognize that they have failed, but they are very reluctant to criticize them openly. So, that seems to me to be a problem for the region.

How does the Nicaraguan dictatorship fit into the club of state dictatorships with Cuba and Venezuela?

It's the most abusive because it's a personal, dynastic, family dictatorship, with total thought-police aspects. It's simply a Daniel Ortega power project. There is no parallel myth of a Chávez or a Castro, of a redeemer. It is simply repression, and in that sense it seems to me that the Nicaraguan dictatorship belongs more in Latin America's past than in the future.

What worries me, in terms of authoritarian tendencies in Latin America, are people like Nayib Bukele [in El Salvador], who has revealed himself to be an elected autocrat, who is effective in the short term, with a draconian policy against citizen insecurity. It's a model that is very popular, because most Salvadorans were desperate because of the terrible public safety situation. So what I'm seeing is that there are ambitious politicians in Latin America who are not looking at Ortega or Venezuela, they're looking at Bukele as their model to copy.

This article was originally published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by our staff.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense, exiliado en Costa Rica. Fundador y director de Confidencial y Esta Semana. Miembro del Consejo Rector de la Fundación Gabo. Ha sido Knight Fellow en la Universidad de Stanford (1997-1998) y profesor visitante en la Maestría de Periodismo de la Universidad de Berkeley, California (1998-1999). En mayo 2009, obtuvo el Premio a la Libertad de Expresión en Iberoamérica, de Casa América Cataluña (España). En octubre de 2010 recibió el Premio Maria Moors Cabot de la Escuela de Periodismo de la Universidad de Columbia en Nueva York. En 2021 obtuvo el Premio Ortega y Gasset por su trayectoria periodística.

PUBLICIDAD 3D