21 de noviembre 2022

The Return of the Military

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

The international lawyer considers that Ortega's mistakes and the growing international pressure will have “unpredictable consequences for the regime”

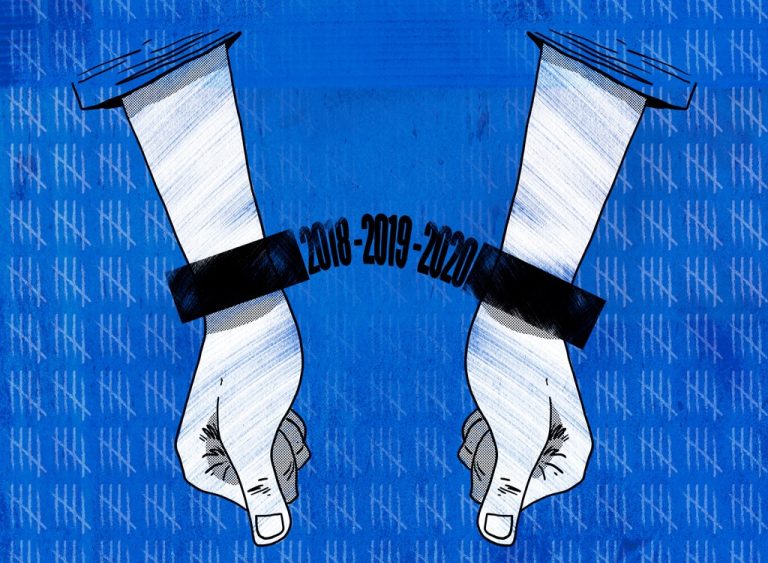

Despite the radicalization of the Ortega Murillo regime’s repression, international lawyer Jared Genser, defender of political prisoners Felix Maradiaga and Juan Sebastian Chamorro, both aspiring presidential candidates, is “cautiously optimistic” about the possibility of freeing his clients and all political prisoners.

Genser, whom The New York Times has dubbed “The Extractor” for his work rescuing political prisoners in 25 different countries under autocratic regimes, is aware that in Nicaragua there are no “legal resources” to defend prisoners of conscience, and that the regime does not respect the mandate of international courts. “In my experience, dictators only release political prisoners when they have to. They don't do it when they want to but when they're put into a situation where many worse things will happen if they don't release political prisoners, if it's a choice between their survival and releasing political prisoners, they will release political prisoners.”

The international lawyer admits in this interview that Nicaragua is “not there yet. There's a lot more work to be done,” but he highlights the consensus and growing pressure from the international community to free the prisoners. “Ortega is making a lot of mistakes,” he says, the pressure will continue to increase and “will have exponential and unpredictable consequences” for the regime.

“It is hard to know what will be the trigger” that will force Ortega to reconsider his position on political prisoners, says Genser, although he warns that “the democratization of Nicaragua is a more complex challenge, which will only be achieved in the long term.”

This matches the number of days they were originally detained incommunicado and is of enormous concern. And so we're obviously calling for immediate transparency and accountability for proof of life and for immediate access to be restored to all of the prisoners and to their families and their lawyers.

With respect to the broader issue of the situation of political prisoners, we're now at more than 220 political prisoners in the country and several dozen detained just in the run-up to the most recent municipal elections. And while obviously, that is incredibly disturbing and upsetting, what I can say from my perspective is that the pressure is undoubtedly building from the international community in ways that make me cautiously optimistic that we will get to a place where the Ortega regime will need to begin to release political prisoners. We're not there yet. We still have a long way to go. But the world is coming together to send a very clear signal to Daniel Ortega, his wife, that the current trajectory is simply unacceptable.

In all these kinds of cases, one needs to proceed in a way that understands that there are generally no legal remedies that are available domestically. Of course, the legal process has been a travesty of justice. The charges against Félix, Juan Sebastian, and really all the political prisoners are obviously fabricated and in violation of their rights to freedom of opinion, expression, peaceful assembly, and political participation.

At the international level, of course, we have had the Inter-American Court of Human Rights demanding their release, and a number of their releases as well. But ultimately, we're not going to resolve this case through legal remedies. We really need to combine those legal decisions with our political and public relations advocacy and dramatically elevate the costs to Ortega and his regime dramatically above the benefits.

In my experience, dictators only release political prisoners when they have to. They don't do it when they want to but when they're put into a situation where many worse things will happen if they don't release political prisoners. If it's a choice between their survival and releasing political prisoners, they will release political prisoners. We're not there yet. There's a lot more work to be done, but I am pleased with the kind of pressure being brought by the international community in a wide array of ways, which I believe is definitely being felt by the Ortega regime.

Well, clearly not yet. But at the same time, it was very interesting to see the United States most recently decided to impose sanctions on the gold sector and sanctioned 500 people in a single day. And I think that demonstrates that the United States is one illustration, working with the EU and other partners, and are now engaging in an exponential escalation of the pressure they're going to put on Ortega. What we have seen is incremental pressure being raised, and in my experience going up against dictators in Latin America and beyond, Incremental pressure doesn't change the views of dictators. I think that once those consequences start to become exponential and unpredictable, this is when dictators have to start to think twice about what they do next. And the fact that the United States has started in the gold sector means that they could go to the meat sector next. They could go to any other sector of the economy.

At the end of the day, when a regime no longer has the money to pay the military, the security forces and the police, that is when they're at risk of losing control. And what I would say is that from what I've observed, there are a lot of sources of money from multilateral institutions, for example, that are drying up. China and Russia are providing moral support, but not financial support to Ortega. And unlike a country like Venezuela, which has unlimited natural resources, Ortega doesn't have the kind of natural resources in Nicaragua that would enable him to hold on for an indefinite period of time. So, I think that when you see things like the resolution in the OAS, General Assembly passing by consensus, when you see the U.N. Human Rights Council creating this group of experts, human rights experts on Nicaragua by consensus, right, it demonstrates that Ortega is out of friends.

And now the question is, what will the international community do next? But if I were Ortega, I would be very worried right now, because there's no telling what's going to happen next. It's no longer going to be predictable and incremental. It's quite clear that the international community, despite the distractions of what's happening in Ukraine and might have taken a lot of public attention that the United States, Canada, Spain, and the EU, are all paying very close attention to what's happening in Nicaragua and are very disturbed by the approach of the Ortega-Murillo regime.

So, from the discussions that we're having all over the world, there are a lot of things that I can't speak about now but that I know people are talking about that are going to stun and scare Ortega, and he's going to have to start to make some very difficult decisions about what's more important. Him staying in power or releasing political prisoners. And I think that when it comes down to those kinds of questions, most dictators, in my experience, choose to release political prisoners rather than put their own ability to stay in power at risk.

The IMF is not a human rights organization. And so to me, reading the most recent IMF report, there was nothing surprising for me there. It was disappointing, but it was predictably disappointing. The IMF puts on blinders and says: we're going to look at institutions of government that relate to the economy and we're going to assess our views of where things are at. The IMF doesn't have enormous resources to rescue Ortega, and I don't believe they're going to spend enormous resources to rescue Ortega. The Central American Integration Bank has been spending more money. But I know there's a lot of pressure on member states of the BCI to slow or stop that flow of funds. And the reality is the economy in Nicaragua is not good and it's getting worse. And when you start to see sectoral sanctions being imposed, I would be surprised if other governments and multilateral institutions don't follow in the footsteps of the United States and expand to other sectors as well.

People have been talking a lot about the return to power of leftist governments in countries like Colombia and Brazil, and Chile. And undoubtedly Ortega will have more friends in the region. But having moral support is not the same thing as having financial support. And I don't see any of those countries or governments being prepared to step up and provide financial support to Ortega. And even though you have new governments in those countries, also Honduras as well, those countries haven't raised their hand and objected to resolutions passing the General Assembly of the OAS or passing the U.N. Human Rights Council and so forth. We hope that those governments, the four governments I mentioned, as well as Mexico, in light of its orientation on Nicaragua, will reach out through the channels they have to say to Ortega, this is just not a sustainable path for you. And there's only so much we can do to help. So help us help you. Let's get to a better place here.

So I'm more optimistic about the likelihood of the release of political prisoners in the foreseeable future. Obviously, the broader and longer-term problems of Nicaragua relating to democratization and restoration of human rights are a longer-term struggle. But it's quite clear to me that the escalation of the focus on Daniel Ortega and his regime and their bad acts is accelerating. And the process of the U.N. is going to help with that enormously because there's now this group, the three-member group of human rights experts that are engaging in wide consultations and gathering information and support. And I would be surprised if their report is not damning of Ortega and his regime. And this will create further momentum at the U.N. for momentum within the OAS system and so forth.

In the short term, for any family, this is incredibly upsetting, disturbing, and worrying, and there's very little that you can say to the family of a political prisoner right now who's been isolated for that long. After having worked against probably about 25 authoritarian regimes over my 20-year career, have a different point of view that is not exclusively or narrowly focused on Nicaragua. But it's put in the context of how these things have played out in my experience in many other places, including many other places in Latin America.

And what I would say is that these are the kinds of things, kinds of mistakes the dictators make that make my work a lot easier. And so, obviously, we're calling for proof of life. The irony is it would help Daniel Ortega to allow access to these prisoners immediately, not hurt him. It would help him because there is going to be pressure building and growing higher and higher and more draconian consequences coming down.

The longer that he tries to maintain this kind of posture, which, as you say, violates the Nelson Mandela Rules, the fair minimum rules for the treatment of prisoners of the U.N. And nobody is defending the way he's treating the prisoners.

I think that the consequences are only going to be more surprising and more dramatic from here. And, at a certain point, Ortega is going to have to make some tough decisions about what he wants to do. He may not be there yet, but if he thinks he can maintain this path, best of luck. My own experience has been going up against 25 dictatorships around the world over my career that you can only treat people this way for a certain period of time when you don't have unlimited natural resources and that the consequences are going to be growing for him and not in the long term, but in the near to medium term. So I think, again, we're not there yet where we need to be. And I understand why families are feeling so upset and despondent right now.

But what I would say is that the international community is paying attention, and is focused on it. Actions are being taken, more needs to be done. And we're going to keep at it until all the prisoners are free.

I'm sure that that's what they're going to focus on. And I think if you look at all the other U.N. commissions on Venezuela, Burma, Myanmar, and so forth, they have highly professionalized staff at the Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights. And it's a strong group of experts that have been appointed to this role. And I expect they're going to try to shine a very bright light on what's going on.

It's really hard to predict what the impact of their work will be. That kind of information, when it gets assimilated into the UN system, becomes a very, very strong tool to facilitate action in other contexts.

My view is that in Nicaragua you need a whole system approach to addressing the crisis in Nicaragua. And by that, what I mean is, not just the U.N. Human Rights Council, but the U.N. General Assembly, and the U.N. Security Council. You need regional organizations like the Organization of American States. You need multilateral lending institutions. You need governments and other multilateral institutions around the world all understanding the facts the same way, and understand violations the same way. And then with that evidence and information, making collective decisions about what's the right way to put maximum pressure to compel Ortega and his regime to change course. And I think that the report that will come out next March, I think will be very, very blunt and objective and devastating by equal measures. And I think that that will then be able to create a lot more momentum for action by the international community.

Representing two of the more than 220 political prisoners, Juan Sebastian Chamorro and Félix Maradiaga, and knowing of the suffering of their own families firsthand based on our ongoing work together, Everything I've described is of no consolation in light of the dramatic urgency to access them and to get them and all of the others out.

So I don't want to overstate my view of the trajectory here, because I understand the suffering of the families is daily suffering and is devastating. At the same time, when I look at the overall trajectory in Nicaragua and the way that we've seen the expansion of international engagement, the way that I've heard from governments and multilateral institutions about the ideas that they're kicking around as to what they're going to do next, I think a number of them are going to be quite surprising to Ortega and his regime and also have an enormous impact. And so, I think that it will take time to start to think very long and hard about how far he's prepared to go here because, at a certain point, it's no longer within the control of the dictator. And the actions of the international community can have irreversible consequences, which may not be entirely predictable. But I think that we just have to keep up the effort, stay strong, keep fighting, and do everything we can to keep the spotlight on the political prisoners and their families. And I know Vicky Cardenas and Berta Valle, the wives respectively of Juan Sebastian Chamorro and Felix Maradiaga, are not giving up. I'm not giving up. We're going to keep fighting till they're free.

My prediction is sooner rather than later, sooner than people are thinking because I just think that at a certain point this becomes very difficult to sustain. Nicaragua is a small country relative to Venezuela and relative to any country in the world. It's a very, very small country. And therefore, the impact that one can have by taking policy actions like the United States and others are taking is much more quick and much more hard-hitting. And so I think a combination of the impunity with which Ortega is acting and the multitude of mistakes that he is making in terms of how he's mistreating the political prisoners, holding them incommunicado, denying them Bibles, kicking out the nuncio, imprisoning Catholic priests, combined with the determination of many important states to focus on this situation and to hold Ortega and Murillo accountable, means that the prospects for a positive resolution, at least as it relates to the political prisoners, is possible in the near to medium term. These kinds of things can happen in a snap of one's fingers.

It really it's hard to know what will be the trigger that will make Ortega reconsider his position. At the end of the day, as I said, my own experience is that you have to elevate the cost of taking your prisoners dramatically above the benefits. And I think that Ortega and Murillo are not irrational actors. And I think that if it's a choice between staying in power and releasing the political prisoners, then they would make the choice to release the political prisoners, even if they do not want to do so.

As I said, my view of the prospects of the long-term democratization of Nicaragua and working through all the challenges that the country is facing in that regard, is definitely not something that I believe is going to be able to be worked out in the near term. It's going to be a much harder and longer struggle. But my focus is much more narrowly on the political prisoners and their families and getting them relief as soon as possible. And I think that is something that is achievable in the short to medium term.

This article was originally published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by Our Staff

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense, exiliado en Costa Rica. Fundador y director de Confidencial y Esta Semana. Miembro del Consejo Rector de la Fundación Gabo. Ha sido Knight Fellow en la Universidad de Stanford (1997-1998) y profesor visitante en la Maestría de Periodismo de la Universidad de Berkeley, California (1998-1999). En mayo 2009, obtuvo el Premio a la Libertad de Expresión en Iberoamérica, de Casa América Cataluña (España). En octubre de 2010 recibió el Premio Maria Moors Cabot de la Escuela de Periodismo de la Universidad de Columbia en Nueva York. En 2021 obtuvo el Premio Ortega y Gasset por su trayectoria periodística.

PUBLICIDAD 3D